Part V: Performance, Concurrency, and Debugging

Part V of this guide delves into advanced topics that are crucial for writing efficient, concurrent, and debuggable Python code. It covers the intricacies of Python’s concurrency model, performance optimization techniques, and tools for logging, debugging, and introspection. By mastering these concepts, you will be well-equipped to tackle complex applications and systems programming in Python.

Table of Contents

13. Concurrency, Parallelism, and Asynchrony

- 13.1. The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) - Explains the Global Interpreter Lock’s role in CPython, how it serializes bytecode execution, and its impact on multithreaded performance.

- 13.2. Multithreading vs. Multiprocessing - Compares

threadingandmultiprocessingmodules in terms of shared memory, communication overhead, and use cases for I/O‑bound vs CPU‑bound tasks. - 13.3. Futures & Task Executors - Describes the

concurrent.futuresabstraction for thread and process pools, including how tasks are scheduled and results retrieved. - 13.4. Asynchronous Programming: async/await - Covers the syntax and semantics of coroutine functions, awaitables, and how the interpreter transforms

async definto state‑machine objects. - 13.5. The Event Loop of

asyncio- Detailsasyncio’s event loop implementation, including selector‑based I/O multiplexing, task scheduling, and callback handling. - 13.6. Emerging GIL-free Models - Summarizes ongoing efforts to introduce subinterpreters with isolated GILs and experimental GIL‑free Python interpreters.

14. Performance and Optimization

- 14.1. Finding Bottlenecks - Introduces

cProfileand third‑party tools likeline_profilerto identify CPU and line‑level bottlenecks in Python code. - 14.2. Numerics with NumPy Arrays - Explains how NumPy’s array operations leverage C‑level optimizations for numerical computing, including broadcasting, vectorization, and memory layout.

- 14.3. Pythonic Optimizations - Shares idiomatic patterns—such as list comprehensions, generator expressions, and built‑in functions—that yield significant speed‑ups.

- 14.4. Native Compilation - Explores how Cython, Numba, and PyPy JIT compilation can accelerate hotspots, including integration patterns and trade‑offs.

- 14.5. Useful Performance Decorators - Demonstrates reusable decorator patterns for caching, memoization, and lazy evaluation to simplify optimization efforts.

15. Logging, Debugging and Introspection

- 15.1. Logging Done Properly:

logging- Introduces theloggingmodule as a high‑level debugging tool, explaining how it provides a flexible framework for emitting diagnostic messages with varying severity levels, destinations, and formats. Rejectprint()return to logging. - 15.2. Runtime Object Introspection:

dir(),inspect- Shows how to retrieve source code, signature objects, and live object attributes for runtime analysis and tooling. - 15.3. Runtime Stack Frame Introspection - Explains accessing and modifying call stack frames via

sys._getframe()and frame attributes for advanced debugging. - 15.3. Interpreter Profiling Hooks - Describes how to attach tracing functions with

sys.settrace()and profiling callbacks withsys.setprofile()for line‑level instrumentation. - 15.4. C‑Level Debugging - Introduces using GDB or LLDB to step through CPython’s C source, leveraging debug builds and Python symbols.

- 15.4. Diagnosing Unexpected Crashes:

faulthandler- Covers utilities likefaulthandlerfor dumping C‑level tracebacks on crashes andpydevdfor remote debugging. - 15.5. Building Custom Debuggers - Guides creation of bespoke debuggers and instrumentation tools using Python’s introspection hooks and C APIs.

13. Concurrency, Parallelism, and Asynchrony

Modern computing thrives on the ability to perform multiple operations seemingly simultaneously. In Python, achieving this involves a nuanced understanding of concurrency, parallelism, and asynchrony – terms often used interchangeably but possessing distinct meanings and implementation strategies. This chapter will dissect CPython’s approach to these concepts, from the infamous Global Interpreter Lock to the cutting-edge asynchronous programming models, providing you with the expertise to design and implement highly performant concurrent applications.

13.1. The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) is a mutex that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple native threads from executing Python bytecodes at once. In CPython, the GIL ensures that only one thread can execute Python bytecode at any given time, even on multi-core processors. This design decision simplifies CPython’s memory management by making object allocation and deallocation thread-safe without complex fine-grained locking. Without the GIL, every object’s reference count would need to be protected by a lock, significantly complicating the interpreter’s internals and introducing substantial overhead.

The immediate consequence of the GIL is that CPython multi-threaded programs cannot fully utilize multiple CPU cores for CPU-bound tasks. If you have a Python program that spends most of its time performing intensive calculations (e.g., numerical processing, complex algorithms), running it with multiple threads will not make it faster; in fact, the overhead of context switching between threads might even make it slower. The GIL prevents true parallelism at the bytecode execution level within a single CPython process.

However, the GIL is released during I/O operations (e.g., reading/writing from disk, network communication, waiting for user input) and when C extension modules (like NumPy or SciPy) perform long-running computations in C code that explicitly release the GIL. This is a crucial distinction: for I/O-bound workloads, where threads spend most of their time waiting for external resources, the GIL’s impact is significantly mitigated. While one thread is blocked on I/O and has released the GIL, another Python thread can acquire the GIL and execute bytecode. This allows multi-threading to effectively achieve concurrency for I/O-bound tasks in CPython.

It’s important to note that the GIL is a specific implementation detail of CPython, not a fundamental part of the Python language specification itself. Other Python implementations, such as Jython (which runs on the JVM) and IronPython (which runs on .NET), do not have a GIL and can achieve true multi-core parallelism with threads. Nevertheless, for the vast majority of Python users running CPython, understanding the GIL’s implications is paramount for choosing the correct concurrency strategy.

13.2. Multithreading vs. Multiprocessing

Given the GIL’s constraint on CPU-bound multi-threading, Python offers distinct modules for achieving concurrency and parallelism: threading for thread-based concurrency and multiprocessing for process-based parallelism. The choice between them hinges on whether your workload is primarily I/O-bound or CPU-bound.

The threading module allows you to create and manage threads within a single Python process. Threads within the same process share the same memory space, which makes data sharing between them straightforward (though requiring careful synchronization to avoid race conditions). This shared memory is both a blessing and a curse: it’s efficient for communication but prone to bugs if not properly managed with locks, semaphores, or other synchronization primitives. Due to the GIL, threading is best suited for I/O-bound tasks. When a thread performs an I/O operation (e.g., time.sleep(), network request, file read), it temporarily releases the GIL, allowing another Python thread to acquire it and execute. This way, while one thread is waiting, others can make progress, leading to effective concurrency.

import threading

import time

def io_bound_task():

print(f"Thread {threading.current_thread().name}: Starting I/O operation...")

time.sleep(2) # Simulates I/O wait, GIL is released

print(f"Thread {threading.current_thread().name}: I/O operation complete.")

threads = [threading.Thread(target=io_bound_task, name=f"Thread-{i}") for i in range(3)]

start_time = time.time()

for t in threads:

t.start() # Start each thread

for t in threads:

t.join() # current (main) thread will wait for the target thread to finish executing

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Total time with threads (I/O bound): {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Output:

# Thread Thread-0: Starting I/O operation...

# Thread Thread-1: Starting I/O operation...

# Thread Thread-2: Starting I/O operation...

# Thread Thread-0: I/O operation complete.

# Thread Thread-1: I/O operation complete.

# Thread Thread-2: I/O operation complete.

# Total time with threads (I/O bound): 2.01 seconds

In contrast, the multiprocessing module creates new processes, each with its own independent Python interpreter and its own GIL. Because processes have separate memory spaces, they are not constrained by the GIL and can achieve true CPU-bound parallelism. Communication between processes requires explicit mechanisms like pipes, queues, or shared memory (though the latter is more complex). The overhead of creating processes is significantly higher than creating threads, and inter-process communication is more complex than shared memory access. However, for tasks that are computation-intensive and can be broken down into independent sub-problems, multiprocessing is the way to go.

When using Python’s multiprocessing module — particularly on Windows or macOS — it’s essential to place process-spawning code inside an if __name__ == "__main__" block. This is because these platforms use the “spawn” method to create new processes, which involves importing the main script as a module in each child process. If the top-level code (such as creating or starting processes) is not protected by this __main__ check, it will execute again in each subprocess during import, leading to infinite recursion or unexpected behavior.

import multiprocessing

import time

def cpu_bound_task():

print(f"Process {multiprocessing.current_process().name}: Starting CPU-bound computation...")

_ = sum(i * i for i in range(10_000_000)) # Simulates CPU-bound work

print(f"Process {multiprocessing.current_process().name}: CPU-bound computation complete.")

# Note: This block is necessary to avoid recursive process creation on Windows and macOS

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Create and start multiple processes

processes = [multiprocessing.Process(target=cpu_bound_task, name=f"Process-{i}") for i in range(3)]

start_time = time.time()

for p in processes:

p.start()

for p in processes:

p.join()

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Total time with processes (CPU bound): {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Expected output: Time will be roughly (single process time) / (number of cores)

# Process Process-0: Starting CPU-bound computation...

# Process Process-1: Starting CPU-bound computation...

# Process Process-2: Starting CPU-bound computation...

# Process Process-1: CPU-bound computation complete.

# Process Process-2: CPU-bound computation complete.

# Process Process-0: CPU-bound computation complete.

# Total time with processes (CPU bound): 0.62 seconds

In summary, choose threading for I/O-bound tasks where shared memory is beneficial and GIL overhead is acceptable due to I/O waits. Choose multiprocessing for CPU-bound tasks where true parallelism is required, accepting the higher overhead of process creation and inter-process communication.

13.3. Futures & Task Executors

Managing threads and processes directly can become cumbersome, especially for complex task scheduling and result retrieval. Python’s concurrent.futures module provides a higher-level abstraction over threading and multiprocessing, simplifying the management of concurrent and parallel tasks. It introduces the concept of Executors and Futures.

An Executor is a high-level interface for asynchronously executing callables. concurrent.futures provides two concrete Executor classes:

ThreadPoolExecutor: Uses a pool of threads. Best for I/O-bound tasks where GIL release during waits allows concurrency.ProcessPoolExecutor: Uses a pool of processes. Best for CPU-bound tasks where true parallelism is needed, bypassing the GIL.

When you submit a task (a callable with arguments) to an Executor, it immediately returns a Future object. A Future represents the eventual result of an asynchronous computation. It’s a placeholder for a result that may not yet be available. You can then query the Future object to check if the computation is done, retrieve its result (which blocks until the result is ready), or retrieve any exception that occurred during the computation.

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor, ProcessPoolExecutor

import time

def long_running_io(name):

print(f"Task {name}: Starting I/O...")

time.sleep(1)

print(f"Task {name}: Finished I/O.")

return f"Result from {name}"

def long_running_cpu(name):

print(f"Task {name}: Starting CPU...")

_ = sum(i * i for i in range(10_000_000))

print(f"Task {name}: Finished CPU.")

return f"Result from {name}"

# Need to protect the entry point for ProcessPoolExecutor as it uses multiprocessing

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Using ThreadPoolExecutor for I/O-bound tasks

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=3) as executor:

futures_io = [executor.submit(long_running_io, f"IO-Task-{i}") for i in range(5)]

for future in futures_io:

print(future.result()) # Blocks until each result is ready

print("\n--- Switching to ProcessPoolExecutor ---\n")

# Using ProcessPoolExecutor for CPU-bound tasks

with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=3) as executor:

futures_cpu = [executor.submit(long_running_cpu, f"CPU-Task-{i}") for i in range(5)]

for future in futures_cpu:

print(future.result()) # Blocks until each result is ready

Note that a ProcessPoolExecutor need to be protected by the if __name__ == "__main__": block to prevent recursive process creation on Windows and macOS, as discussed in the previous section.

The concurrent.futures module also provides as_completed(), an iterator that yields Futures as they complete, allowing you to process results as they become available without blocking on any single task. This abstraction simplifies common concurrency patterns, such as fan-out/fan-in, where a main process or thread distributes tasks to a pool and collects their results. It elegantly handles thread/process lifecycle management, queueing, and result retrieval, providing a high-level abstraction of concurrency.

13.4. Asynchronous Programming: async/await

Beyond threads and processes, Python offers a powerful single-threaded concurrency model known as asynchronous programming, primarily facilitated by the asyncio module and the async/await syntax. This model is exceptionally well-suited for I/O-bound and high-concurrency workloads where the GIL is a bottleneck for multi-threading. Instead of relying on OS threads, asyncio uses a single event loop to manage multiple concurrent operations.

The async and await keywords are syntactic sugar introduced in Python 3.5 that define coroutines. A coroutine is a special type of function that can be paused and resumed.

async defdefines a coroutine function. When called, it doesn’t execute immediately but returns a coroutine object.awaitis used within anasync deffunction to pause its execution until anawaitable(another coroutine, a Future, or a Task) completes. Whenawaitis called, the current coroutine yields control back to the event loop, allowing the event loop to run other tasks while the awaited operation (e.g., a network request) is pending.

Mental Diagram: Coroutine as a State Machine

Imagine a coroutine function (defined with async def) as a sophisticated state machine.

+------------------+ +----------------+

| Initial State | --> | Running State |

|(Coroutine Object)| |(Executing Code)|

+------------------+ +----------------+

^ |

| | await

| return v

| +----------------+

| | Paused State |

+--------------- |(Yields Control)|

+----------------+

When a coroutine is awaited, it changes from a running state to a paused state, yielding control. The event loop can then pick up another task that is ready to run. Once the awaited operation completes (e.g., data arrives over the network), the event loop resumes the paused coroutine from where it left off. This non-blocking I/O allows a single thread to manage thousands of concurrent connections efficiently, as it never idles waiting for I/O; instead, it switches to another ready task.

13.5. The Event Loop of asyncio

The event loop is the heart of asyncio. It’s a single-threaded loop that continuously monitors and dispatches events. Its primary role is to manage and run coroutines and perform non-blocking I/O operations. The event loop registers I/O operations (like reading from a socket) with the operating system using mechanisms like select, epoll, or kqueue (multiplexing I/O). When an I/O operation completes, the OS notifies the event loop, which then resumes the corresponding paused coroutine.

The lifecycle of an asyncio application typically involves:

- Creating coroutine objects (by calling

async deffunctions). - Creating

asyncio.Taskobjects from these coroutines. Tasks are essentially wrappers around coroutines that the event loop schedules. - Running the event loop (e.g.,

asyncio.run()orloop.run_until_complete()) which then manages the execution of these tasks.

asyncio also provides a rich set of concurrency control patterns, similar to those found in multi-threading, but adapted for the asynchronous model:

asyncio.gather(): Runs multiple coroutines concurrently and waits for all of them to complete, collecting their results. This is similar toThreadPoolExecutor.map()but for coroutines.asyncio.Queue: An asynchronous, coroutine-safe queue for distributing work between tasks. Unlikequeue.Queuefrom thequeuemodule, it usesasync/awaitfor itsputandgetoperations, making them non-blocking.asyncio.Lock,asyncio.Semaphore,asyncio.Event,asyncio.Condition: These provide synchronization primitives for managing shared resources between concurrently running coroutines within the single event loop thread. They ensure that even within a single thread, data is accessed safely and operations are ordered correctly. For example,asyncio.Lockensures that only one coroutine can access a critical section of code at a time, preventing race conditions that could arise from context switching between coroutines.

import asyncio

import time

async def worker(name, delay):

print(f"Worker {name}: Starting (delay={delay}s)")

t = time.time()

await asyncio.sleep(delay) # Non-blocking sleep, yields control

print(f"Worker {name}: Finished after {time.time() - t:.2f} seconds")

return f"Result {name}"

async def main():

# Run multiple workers concurrently

results = await asyncio.gather(

worker("A", 3),

worker("B", 1),

worker("C", 2)

)

print(f"All workers finished. Results: {results}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

# Output:

# Worker A: Starting (delay=3s)

# Worker B: Starting (delay=1s)

# Worker C: Starting (delay=2s)

# Worker B: Finished after 1.01 seconds

# Worker C: Finished after 2.01 seconds

# Worker A: Finished after 3.01 seconds

# All workers finished. Results: ['Result A', 'Result B', 'Result C']

Mastering asyncio and its patterns is key to building highly performant, scalable I/O-bound applications in Python, such as web servers, network clients, and data pipelines that interact heavily with external services. It allows for high concurrency with minimal overhead compared to multi-threading for such workloads.

13.6. Emerging GIL-free Models

While the GIL has served CPython well by simplifying its internal design and enabling efficient I/O-bound concurrency, its limitation on true CPU parallelism remains a significant challenge. The Python community and core developers are actively exploring and implementing new models to address this.

One promising approach is subinterpreters. A subinterpreter is an independent, isolated Python interpreter running within the same process. Critically, each subinterpreter would have its own GIL. This means you could potentially run multiple subinterpreters concurrently on different CPU cores, each executing Python bytecode in parallel, without the complex inter-thread locking issues that a single GIL prevents. Communication between subinterpreters would require explicit mechanisms, similar to inter-process communication, ensuring their isolation. This model aims to provide true parallelism within a single process while retaining the benefits of the GIL for individual subinterpreters.

Historically, even when multiple subinterpreters were created, they still shared the single, process-wide Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), meaning they could not execute Python bytecode in true CPU parallelism. However, significant ongoing work, formalized in PEP 684 – A Per-Interpreter GIL, is set to change this fundamental limitation. The core idea is to transform the GIL from a global lock that applies to the entire process into a lock that is specific to each individual interpreter. This architectural shift means that in future Python versions (with Python 3.13 and beyond being key development targets), it will become possible for multiple subinterpreters to run concurrently on different CPU cores, each executing Python bytecode in parallel because they each possess their own distinct GIL.

Another area of active research and development involves GIL-free Python interpreters. Projects like the “nogil” fork of CPython (initially by Sam Gross) aim to remove the GIL entirely from the CPython core. This is an immensely complex undertaking, as it requires re-architecting CPython’s fundamental memory management and object access to be thread-safe without the GIL. This typically involves introducing fine-grained locking mechanisms or adopting alternative concurrency control strategies (e.g., atomic reference counting, hazardous pointers). While a truly GIL-free CPython would unlock unprecedented CPU parallelism for multi-threaded Python code, it comes with potential trade-offs:

- Performance Impact: Fine-grained locking can introduce overhead, potentially making single-threaded or I/O-bound multi-threaded code slower.

- Backward Compatibility: Changes to the C API for extensions might be necessary, posing challenges for existing libraries.

- Complexity: The internal complexity of the interpreter would increase significantly.

While a complete GIL removal is a long-term goal with many hurdles, the “nogil” work continues to inform the core development team and influence future versions of CPython. The trajectory suggests a future where Python offers more robust and performant options for true CPU parallelism, likely through a combination of enhanced subinterpreters and potentially selective GIL removal for specific internal components or object types, rather than a single, universal solution. As an advanced developer, staying abreast of these emerging models is crucial for anticipating future architectural possibilities and best practices in Python.

Key Takeaways

- Global Interpreter Lock (GIL): A mutex in CPython that ensures only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time. It simplifies CPython’s memory management but limits CPU-bound parallelism in multi-threaded Python.

- Threads (

threading): Best for I/O-bound concurrency. Threads share memory, allowing GIL to be released during I/O waits, enabling other threads to run. Communication is easy but requires careful synchronization. - Processes (

multiprocessing): Best for CPU-bound parallelism. Each process has its own interpreter and GIL, achieving true parallelism on multi-core CPUs. Higher overhead for creation and communication. - Futures & Executors (

concurrent.futures): A high-level abstraction usingThreadPoolExecutor(for threads) andProcessPoolExecutor(for processes) to manage pools of workers. Tasks are submitted, returningFutureobjects for result retrieval and simpler task management. - Asynchronous Programming (

async,await,asyncio): A single-threaded, event-loop-driven concurrency model ideal for I/O-bound and high-concurrency workloads.async defdefines coroutines,awaitpauses execution, yielding control to the event loop. - Event Loop: The core of

asyncio, managing non-blocking I/O and scheduling coroutines. Provides asynchronous versions of concurrency control primitives (e.g.,asyncio.Lock,asyncio.Queue). - Emerging Models:

- Subinterpreters: Independent Python interpreters within the same process, each with its own GIL, aiming for true parallelism with isolated memory spaces.

- GIL-free Proposals: Efforts to remove the GIL entirely from CPython, a complex undertaking that could unlock full multi-core CPU parallelism but poses significant challenges for performance and compatibility.

14. Performance and Optimization

Optimizing Python code for performance is an advanced skill that requires a deep understanding of its execution model. It’s a nuanced process, often more about identifying and addressing bottlenecks than blindly rewriting code. While Python’s dynamic nature and high-level abstractions sometimes come with a performance cost compared to lower-level languages, strategic optimization can yield substantial improvements. This chapter will equip you with the tools and techniques to identify performance hotspots, apply Pythonic optimization patterns, leverage native compilation, and use decorators for common performance enhancements, enabling you to write highly performant and efficient Python applications.

14.1. Finding Bottlenecks

The first and most critical rule of optimization is: Don’t optimize without profiling. Premature optimization is the root of much evil. Performance problems rarely reside where you intuitively expect them. Profiling is the systematic process of collecting data about your program’s execution, revealing where it spends most of its time and resources.

Python’s standard library provides cProfile, a C-implemented profiler that offers excellent performance and detailed statistics. cProfile tracks function calls, execution times, and call counts. It provides a summary of “cumulative time” (the total time spent in a function and all functions it calls) and “internal time” (the time spent exclusively within a function, excluding calls to sub-functions). This distinction is vital for pinpointing where the actual work is being done.

import cProfile

import pstats

import time

def function_a(): # line 5

time.sleep(0.1)

function_b()

def function_b(): # line 9

time.sleep(0.05)

_ = [i*i for i in range(10000)] # CPU-bound task

def main(): # line 13

for _ in range(5):

function_a()

time.sleep(0.02) # Some other work

if __name__ == "__main__":

profiler = cProfile.Profile()

profiler.enable()

main()

profiler.disable()

stats = pstats.Stats(profiler).sort_stats('cumtime') # Sort by cumulative time

stats.print_stats(4) # Print top 4 results

# stats.dump_stats("profile_results.prof") # Save results to a file

# Then analyze with: python -m pstats profile_results.prof

# Output:

# 23 function calls in 0.780 seconds

# Ordered by: cumulative time

# ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

# 1 0.000 0.000 0.780 0.780 /path/to/module.py:13(main)

# 11 0.775 0.070 0.775 0.070 {built-in method time.sleep}

# 5 0.001 0.000 0.759 0.152 /path/to/module.py:5(function_a)

# 5 0.004 0.001 0.256 0.051 /path/to/module.py:9(function_b)

While cProfile is excellent for function-level analysis, it doesn’t tell you which line within a function is the bottleneck. For that, you need line_profiler (a third-party tool, installable via pip install line_profiler). line_profiler allows you to decorate specific functions, and when profiled, it provides line-by-line timing statistics, showing exactly how much time is spent on each line of code. This granular detail is invaluable for pinpointing the precise hot spots within a function.

To use line_profiler, you decorate the functions you want to analyze with @profile (after importing it from kernprof.py or directly from line_profiler if you use the standalone script). Then, you run your script with kernprof.py -l your_script.py, and inspect the results with python -m line_profiler your_script.py.lprof. Tools like these provide empirical data, transforming optimization from guesswork into a data-driven process, ensuring you focus your efforts where they will have the most impact.

14.2. Numerics with NumPy Arrays

For applications heavily involved in numerical computation, NumPy (Numerical Python) is an absolute game-changer. It provides a powerful array object (the ndarray) that is orders of magnitude faster and more memory-efficient than standard Python lists for storing and manipulating large sets of numerical data. Understanding why NumPy achieves this superior performance is crucial for anyone optimizing numerical workloads in Python.

The primary reason for NumPy’s speed lies in its implementation and design principles. NumPy arrays are stored contiguously in memory, unlike Python lists which store pointers to individual objects scattered across memory. This contiguous layout allows for highly efficient vectorized operations. When you perform an operation on a NumPy array (e.g., addition, multiplication), it’s typically executed as a single, optimized operation on the entire array or subsections of it, often implemented in highly optimized C or Fortran code beneath the surface. This bypasses Python’s interpreter loop overhead for individual elements. Imagine a diagram where a Python list [obj1, obj2, obj3] points to obj1, obj2, obj3 at arbitrary memory locations, whereas a NumPy array [val1, val2, val3] is a solid block of memory containing val1, val2, val3 directly.

This concept of vectorization is key. Instead of writing explicit Python for loops to iterate over elements and perform operations one by one (which is slow due to GIL contention and interpreter overhead), you express operations on entire arrays. NumPy handles the low-level, element-wise computation efficiently in compiled C code. This also extends to broadcasting, a powerful NumPy feature that allows operations between arrays of different shapes, often without needing to copy data, further enhancing efficiency. For any CPU-bound numerical task, particularly those involving large datasets, replacing Python lists and explicit loops with NumPy arrays and vectorized operations is often the single most impactful optimization.

import numpy as np

import time

# --- Performance comparison: Python list vs. NumPy array ---

size = 10_000_000

python_list = list(range(size))

numpy_array = np.arange(size)

# Python list multiplication

start_time = time.time()

python_result = [x * 2 for x in python_list]

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Python list multiplication: {end_time - start_time:.4f} seconds")

# NumPy array multiplication (vectorized operation)

start_time = time.time()

numpy_result = numpy_array * 2

end_time = time.time()

print(f"NumPy array multiplication: {end_time - start_time:.4f} seconds")

# --- Example of Broadcasting ---

arr1 = np.array([1, 2, 3])

arr2 = np.array([[10], [20], [30]]) # Column vector

result_broadcast = arr1 + arr2

print(f"\nBroadcasting example (arr1 + arr2):\n{result_broadcast}")

# Output:

# Python list multiplication: 1.5015 seconds

# NumPy array multiplication: 0.0227 seconds

#

# Broadcasting example (arr1 + arr2):

# [[11 12 13]

# [21 22 23]

# [31 32 33]]

Effective use of NumPy for performance boils down to one guiding principle: vectorize everything possible. This means reframing your algorithms to operate on entire arrays or array slices using NumPy’s functions and operators, rather than iterating with Python for loops. If an operation isn’t directly available in NumPy, consider if it can be composed from existing NumPy functions or if a library built on NumPy (like SciPy for advanced scientific computing or pandas for data analysis) provides the needed functionality. While NumPy arrays are ideal for homogenous numerical data, they are not a drop-in replacement for all list use cases; they excel precisely in the domain of high-performance array computing.

14.3. Pythonic Optimizations

Once profiling has identified a bottleneck, the next step is often to apply Pythonic optimization patterns. These are techniques that leverage Python’s built-in efficiencies and design philosophies to achieve speed-ups without resorting to external compilation or complex C-level code.

-

Leverage Built-in Functions and C-implemented Modules: Python’s built-in functions (e.g.,

sum(),min(),max(),len(),map(),filter()) and standard library modules implemented in C (e.g.,math,collections,itertools,os,sys) are highly optimized. Whenever possible, prefer these over equivalent pure Python implementations, especially for operations on sequences. For instance,sum(my_list)is almost always faster thantotal = 0; for x in my_list: total += x. This is because the C-level implementation avoids the overhead of the Python interpreter’s bytecode dispatch loop for each operation. -

List Comprehensions and Generator Expressions: These are not just syntactic sugar; they are often more efficient than traditional

forloops for creating lists or iterators. List comprehensions are optimized at the C level, reducing interpreter overhead. Generator expressions (which use parentheses instead of square brackets) are even more memory-efficient as they produce items lazily, on demand, making them ideal for large datasets where you don’t need all items in memory simultaneously.

# List comprehension (often faster than explicit loop)

my_list = [i * i for i in range(1_000_000)]

# Generator expression (memory efficient for large datasets)

my_generator = (i * i for i in range(1_000_000))

# Process items one by one:

# for item in my_generator:

# pass

-

Correct Data Structures: Choosing the right data structure can drastically change algorithmic complexity and performance.

- Use

setfor fast membership testing (O(1)average time complexity) instead of lists (O(n)). - Use

dictfor fast key-value lookups (O(1)average) instead of searching lists of tuples. collections.dequeis efficient for fast appends and pops from both ends of a sequence, unlike Python lists which are efficient only at the end.- When concatenating many strings in a loop, prefer

''.join(list_of_strings)over repeated+operations, as string concatenation creates new string objects with each operation.

- Use

-

Avoid Unnecessary Object Creation: Creating and destroying Python objects (even small ones like integers in a loop) incurs overhead. Reusing objects, minimizing temporary variables, and avoiding redundant function calls can sometimes yield micro-optimizations. For example, pre-calculating values outside a loop. However, this should only be done if profiling specifically points to object creation as a bottleneck. These “Pythonic” optimizations focus on working with the interpreter’s strengths rather than against them.

14.4. Native Compilation

For truly CPU-bound bottlenecks that cannot be resolved with Pythonic optimizations, extending beyond the CPython interpreter’s native speed becomes necessary. This often involves leveraging tools that perform native compilation or Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation.

Cython: Cython is a superset of Python that allows you to write Python code with optional static type declarations. It compiles this code directly into highly optimized C/C++ code, which is then compiled into machine code. Cython is particularly effective for:

- Accelerating Python loops: By adding type hints, Cython can eliminate Python object overhead in loops, making them run at C-like speeds.

- Interfacing with C libraries: It simplifies wrapping existing C/C++ libraries for use in Python.

- Optimizing numerical code: Great for operations on NumPy arrays.

Imagine a critical loop where Python is slow due to dynamic typing. In Cython, you can declare variable types (e.g., cdef int i, cdef double x), which allows the compiler to generate more efficient machine code, bypassing the Python interpreter’s bytecode dispatch for those specific operations. This is like drawing a diagram where “Python Code with Type Hints” goes to a “Cython Compiler” which outputs “C Code” which then goes to a “C Compiler” which finally produces “Machine Code”.

# my_module.pyx (Cython file)

def calculate_sum(n):

cdef long long i

cdef long long total = 0

for i in range(n):

total += i * i

return total

# setup.py (for compiling the .pyx file)

from setuptools import setup

from Cython.Build import cythonize

setup(

ext_modules = cythonize("my_module.pyx")

)

# Then run: python setup.py build_ext --inplace

# Now you can import 'my_module' in Python and call calculate_sum()

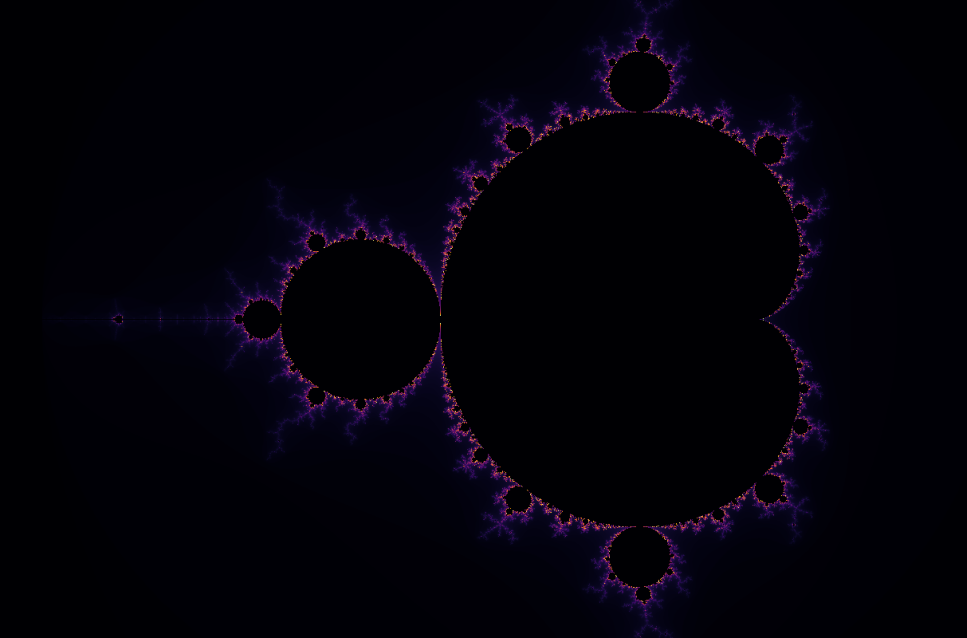

Numba: Numba is a JIT (Just-In-Time) compiler that translates Python code into optimized machine code at runtime, often without requiring any code changes other than adding a decorator. It is specifically designed for numerical algorithms and works best with NumPy arrays. Numba’s @jit decorator (@jit(nopython=True) for maximum performance) allows functions to be compiled directly to native code, bypassing the Python interpreter. This makes it an excellent choice for scientific computing and data processing pipelines. Numba dynamically compiles the function the first time it’s called.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from numba import jit

import time

@jit(nopython=True)

def mandelbrot(width: int, height: int, max_iter: int) -> np.ndarray:

image = np.zeros((height, width), dtype=np.uint8)

for y in range(height):

for x in range(width):

zx = x * 3.5 / width - 2.5 # Real part

zy = y * 2.0 / height - 1.0 # Imaginary part

c = complex(zx, zy)

z = 0.0j

for i in range(max_iter):

z = z * z + c

if (z.real * z.real + z.imag * z.imag) >= 4.0:

image[y, x] = i

break

return image

# Settings

width, height = 1400, 800

max_iter = 256

# First call (includes compilation time)

start = time.time()

image = mandelbrot(width, height, max_iter)

end = time.time()

print(f"First render (includes compile): {end - start:.3f}s")

# Second call (cached and fast)

start = time.time()

image = mandelbrot(width, height, max_iter)

end = time.time()

print(f"Second render (cached JIT): {end - start:.3f}s")

# Show the image

plt.imshow(image, cmap="inferno")

plt.axis("off")

plt.show()

# Output:

# First render (includes compile): 2.004s

# Second render (cached JIT): 0.292s

PyPy: PyPy is an alternative Python interpreter with a built-in JIT compiler. Instead of compiling individual functions, PyPy’s JIT compiles your entire Python application at runtime. This means that hot code paths (frequently executed sections) are identified and translated into highly optimized machine code on the fly. For many pure Python CPU-bound applications, simply running them with PyPy instead of CPython can yield significant speed-ups (often 5x or more) with zero code changes. However, PyPy can have compatibility issues with C extensions that are tightly coupled to CPython’s internals, and its startup time can sometimes be higher for short-lived scripts.

These tools provide different levels of invasiveness and offer trade-offs between effort and potential performance gains. Cython requires explicit type hinting and a build step, Numba is mostly a decorator-based JIT for numerical code, and PyPy is a drop-in replacement interpreter for general speed-ups.

14.5. Useful Performance Decorators

Decorators in Python provide a powerful and elegant way to add functionality to functions or methods without modifying their source code. Several common performance-related patterns can be encapsulated within decorators, making optimization efforts more reusable and cleaner.

Caching/Memoization (functools.lru_cache)

One of the most effective optimization techniques for functions with expensive computations and recurring inputs is memoization (or caching). The functools.lru_cache decorator provides a simple way to cache function results. When a decorated function is called with arguments it has seen before, it returns the cached result instead of re-executing the function body. lru_cache implements a Least-Recently Used (LRU) eviction strategy to manage cache size.

from functools import lru_cache

import time

@lru_cache(maxsize=128) # Cache up to 128 most recently used results

def expensive_computation(n):

print(f"Calculating expensive_computation({n})...")

time.sleep(1) # Simulate expensive work

return n * n + 100

print(expensive_computation(10)) # Calculates

print(expensive_computation(20)) # Calculates

print(expensive_computation(10)) # Fetches from cache, much faster

print(expensive_computation(30)) # Calculates

print(expensive_computation(20)) # Fetches from cache

lru_cache is excellent for pure functions (functions that always return the same output for the same input and have no side effects). For functions with varying arguments or that are called with very diverse inputs, the benefits might be minimal, or the cache size might need careful tuning.

Lazy Evaluation / Property Caching

For class methods that compute a value that won’t change after its first access but might be expensive to calculate, a custom property decorator can implement lazy evaluation and caching. The result is computed only on the first access and then stored as an instance attribute, effectively “caching” it for subsequent accesses without re-computation.

class MyDataProcessor:

def __init__(self, data):

self._data = data

self._expensive_result = None # Initialize cache

@property

def expensive_result(self):

if self._expensive_result is None:

print("Calculating expensive_result for the first time...")

time.sleep(2) # Simulate expensive calculation

self._expensive_result = sum(x * x for x in self._data)

return self._expensive_result

processor = MyDataProcessor(range(10_000_000))

print(f"First access: {processor.expensive_result}") # Calculates

print(f"Second access: {processor.expensive_result}") # Fetches from cache

Timing Decorators

While cProfile and line_profiler are for deep analysis, a simple timing decorator can be useful for quick checks on individual function performance during development.

import time

from functools import wraps

def timeit(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

print(f"Function '{func.__name__}' took {end_time - start_time:.4f} seconds.")

return result

return wrapper

@timeit

def example_function(n):

_ = [i * i for i in range(n)]

example_function(1_000_000)

example_function(5_000_000)

# Output:

# Function 'example_function' took 0.0922 seconds.

# Function 'example_function' took 0.4397 seconds.

These decorators, whether from the standard library or custom-built, provide powerful, non-invasive ways to apply common optimization patterns, making your code cleaner and more performant without significantly altering its core logic.

Key Takeaways

- Profiling First: Always profile your code (

cProfilefor function-level,line_profilerfor line-level) before attempting any optimizations. Focus efforts on identified bottlenecks. - Numpy for Numerical Performance: Use NumPy arrays and vectorized operations for numerical tasks. They are significantly faster than Python lists and loops due to contiguous memory storage and optimized C implementations.

- Pythonic Optimizations:

- Built-ins and C-Modules: Prefer Python’s highly optimized built-in functions and standard library modules implemented in C (e.g.,

sum,itertools,collections). - Comprehensions/Generators: Use list comprehensions for list creation, and generator expressions for memory-efficient iteration, often more performant than explicit loops.

- Correct Data Structures: Choose

setfor fast lookups,dictfor key-value mapping, anddequefor efficient double-ended operations. - Efficient String Concatenation: Use

''.join(list_of_strings)for concatenating many strings.

- Built-ins and C-Modules: Prefer Python’s highly optimized built-in functions and standard library modules implemented in C (e.g.,

- Native Compilation:

- Cython: Compiles Python with optional static type declarations to C/C++ code, then to machine code. Excellent for optimizing critical loops and numerical code, and for C/C++ interfacing.

- Numba: A JIT compiler (using

@jitdecorator) that translates numerical Python code (especially with NumPy) into optimized machine code at runtime. - PyPy: An alternative Python interpreter with a built-in JIT compiler that can significantly accelerate pure Python CPU-bound applications with zero code changes.

- Performance Decorators:

functools.lru_cache: Essential for memoizing (caching) results of expensive, pure functions to avoid redundant computations.- Custom Property Caching: Implement lazy evaluation for class attributes that are expensive to compute once.

- Timing Decorators: Useful for quick performance checks of individual functions during development.

15. Logging, Debugging and Introspection

Understanding Python’s internal architecture is not just for performance optimization; it’s also fundamental to effective debugging and building powerful introspection tools. Python provides a rich set of built-in modules and C-level APIs that allow developers to peer deeply into the runtime state of their programs, analyze execution flow, and even manipulate the interpreter’s behavior. This chapter will guide you through these advanced techniques, from Python-level introspection to C-level debugging, empowering you to diagnose the most elusive bugs and create sophisticated debugging utilities.

15.1. Logging Done Properly: loging

While the low-level introspection and tracing tools discussed in this chapter are invaluable for diagnosing complex, deep-seated issues, everyday debugging and application monitoring primarily rely on a more accessible and robust mechanism: the standard library’s logging module. Unlike print() statements, which are crude and difficult to manage in production, logging provides a flexible and scalable framework for emitting diagnostic messages from your application, allowing for granular control over message severity, destination, and format.

The core concept behind the logging module is the Logger. You obtain a logger instance (typically for each module or subsystem of your application) and use it to emit messages at various severity levels:

DEBUG: Detailed information, typically only of interest when diagnosing problems.INFO: Confirmation that things are working as expected.WARNING: An indication that something unexpected happened, or indicative of some problem in the near future (e.g., ‘disk space low’). The software is still working as expected.ERROR: Due to a more serious problem, the software has not been able to perform some function.CRITICAL: A serious error, indicating that the program itself may be unable to continue running.

Messages below the configured threshold for a logger will simply be ignored, providing a powerful way to control verbosity without modifying code. This allows developers to include extensive debugging messages during development that can be easily suppressed in production by simply changing a configuration setting.

import logging

# Basic configuration: logs to console, INFO level and above

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO, format="%(asctime)s %(name)s: %(levelname)s - %(message)s")

# Get a logger for a specific module or component

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def perform_operation(value):

logger.debug(f"Attempting operation with value: {value}")

if value < 0:

logger.warning("Negative value provided, proceeding with caution.")

try:

result = 10 / value

logger.info(f"Operation successful, result: {result}")

return result

except ZeroDivisionError:

logger.error("Attempted to divide by zero!")

# In a real app, you might raise, return sentinel, etc.

raise

except Exception as e:

logger.critical(f"An unhandled critical error occurred: {e}", exc_info=True) # exc_info to include traceback

raise

if __name__ == "__main__":

perform_operation(5)

perform_operation(-2)

try:

perform_operation(0)

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass # Handle the raised exception so script doesn't crash

# Output:

# 2025-06-22 00:54:12,347 __main__: INFO - Operation successful, result: 2.0

# 2025-06-22 00:54:12,348 __main__: WARNING - Negative value provided, proceeding with caution.

# 2025-06-22 00:54:12,348 __main__: INFO - Operation successful, result: -5.0

# 2025-06-22 00:54:12,348 __main__: ERROR - Attempted to divide by zero!

Architecture of the logging Module

The logging module operates on a modular, hierarchical architecture designed for scalability and flexibility. At its core are four main components:

- Loggers: These are the entry points for your logging calls (e.g.,

logger.info("message")). Loggers are organized in a hierarchical namespace (e.g.,my_app.sub_module). Messages emitted by a child logger will propagate up to its parent loggers, unless propagation is explicitly disabled. Each logger can be assigned a minimum severity level, meaning it will only process messages at or above that level. - Handlers: Once a logger decides to process a message, it passes it to one or more handlers. Handlers are responsible for sending log records to specific destinations. Common handlers include

StreamHandler(for console output),FileHandler(for writing to a file),RotatingFileHandler(for rotating log files by size), andTimedRotatingFileHandler(for rotating log files by time interval). You can attach multiple handlers to a single logger. - Formatters: Handlers use formatters to define the exact layout of a log record in the final output. Formatters use a format string that can include various attributes of the log record, such as timestamp, logger name, level, filename, line number, and the message itself. This allows for consistent and informative log entries.

- Filters: These provide an additional layer of control, allowing you to include or exclude log records based on specific criteria beyond just their level. Filters can be attached to loggers or handlers.

import logging

from logging.handlers import RotatingFileHandler

# 1. Get a logger instance

# Root logger is "root", typically get specific named logger

logger = logging.getLogger("my_application_logger")

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG) # Set minimum level for this logger

# 2. Create Handlers

# Console Handler

console_handler = logging.StreamHandler()

console_handler.setLevel(logging.INFO) # Only INFO and above to console

# File Handler with rotation

log_file = "app.log"

file_handler = RotatingFileHandler(

log_file,

maxBytes=10 * 1024 * 1024, # 10 MB

backupCount=5 # Keep 5 old log files

)

file_handler.setLevel(logging.DEBUG) # All debug messages to file

# 3. Create Formatters

console_formatter = logging.Formatter('%(levelname)s: %(message)s')

file_formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(filename)s:%(lineno)d - %(message)s')

# 4. Attach Formatters to Handlers

console_handler.setFormatter(console_formatter)

file_handler.setFormatter(file_formatter)

# 5. Add Handlers to the Logger

logger.addHandler(console_handler)

logger.addHandler(file_handler)

def complex_operation(data):

logger.debug(f"Received data for complex operation: {data}")

if not isinstance(data, (int, float)):

logger.error(f"Invalid data type for operation: {type(data)}", exc_info=True)

raise TypeError("Data must be numeric.")

if data <= 0:

logger.warning("Non-positive data, potential issues ahead.")

try:

result = 100 / data

logger.info(f"Operation successful. Result: {result:.2f}")

return result

except ZeroDivisionError:

logger.critical("Critical error: Division by zero attempted!", exc_info=True)

raise

except Exception as e:

logger.critical(f"An unexpected error occurred during operation: {e}", exc_info=True)

raise

if __name__ == "__main__":

logger.info("Application starting...")

try:

complex_operation(50)

complex_operation(-10)

complex_operation(0) # causes ZeroDivisionError

complex_operation("text") # causes TypeError

except (TypeError, ZeroDivisionError):

logger.info("Handled expected error. Continuing application flow.")

logger.info("Application finished.")

The console output will look like this:

INFO: Application starting...

INFO: Operation successful. Result: 2.00

WARNING: Non-positive data, potential issues ahead.

INFO: Operation successful. Result: -10.00

WARNING: Non-positive data, potential issues ahead.

CRITICAL: Critical error: Division by zero attempted!

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Users\smoli\tmp\testing.py", line 45, in complex_operation

result = 100 / data

~~~~^~~~~~

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

INFO: Handled expected error. Continuing application flow.

INFO: Application finished.

And the log file app.log will contain:

2025-06-22 01:07:49,646 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:57 - Application starting...

2025-06-22 01:07:49,646 - my_application_logger - DEBUG - testing.py:38 - Received data for complex operation: 50

2025-06-22 01:07:49,647 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:46 - Operation successful. Result: 2.00

2025-06-22 01:07:49,647 - my_application_logger - DEBUG - testing.py:38 - Received data for complex operation: -10

2025-06-22 01:07:49,647 - my_application_logger - WARNING - testing.py:43 - Non-positive data, potential issues ahead.

2025-06-22 01:07:49,647 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:46 - Operation successful. Result: -10.00

2025-06-22 01:07:49,648 - my_application_logger - DEBUG - testing.py:38 - Received data for complex operation: 0

2025-06-22 01:07:49,651 - my_application_logger - WARNING - testing.py:43 - Non-positive data, potential issues ahead.

2025-06-22 01:07:49,651 - my_application_logger - CRITICAL - testing.py:49 - Critical error: Division by zero attempted!

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Users\smoli\tmp\testing.py", line 45, in complex_operation

result = 100 / data

~~~~^~~~~~

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

2025-06-22 01:07:49,662 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:64 - Handled expected error. Continuing application flow.

2025-06-22 01:07:49,662 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:65 - Application finished.

This robust pipeline enables scenarios like sending ERROR messages to an email while sending DEBUG messages to a file, or filtering messages based on custom criteria. For production applications, configuring logging via a file or dictionary (logging.config.fileConfig or logging.config.dictConfig) is preferred, allowing runtime modification without code changes. Adopting the logging module is a fundamental best practice for any serious Python development, providing a clear, configurable, and high-performance way to understand and diagnose your application’s behavior.

Basic and Advanced Configuration

For simple scripts or initial development, the logging module offers a quick and easy way to get started: logging.basicConfig(). This function performs basic configuration for the root logger, typically setting a StreamHandler to stderr and a default formatter. You can specify the level and format directly:

import logging

# Basic configuration: logs INFO and above to console

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO, format='%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) # Get a named logger for the current module

logger.debug("This debug message will not appear by default.")

logger.info("This is an informational message.")

logger.warning("Something potentially problematic happened.")

logger.error("An error occurred during processing.")

logger.critical("Fatal error! System might be shutting down.")

While basicConfig() is convenient, it’s limited. It can only be called once, and it configures the root logger, which might not be ideal for complex applications with multiple components requiring different logging behaviors. For robust, production-grade applications, external configuration is the preferred approach. This allows system administrators or operations teams to adjust logging behavior (levels, destinations, formats) without modifying or redeploying application code.

The logging.config module provides two main ways for external configuration:

logging.config.fileConfig(fname): Reads configuration from a standard INI-format file. This is a very common method for legacy applications or where a simple, text-based configuration is preferred.logging.config.dictConfig(config_dict): Takes a dictionary (often loaded from a YAML or JSON file) as its configuration. This is the more modern and flexible approach, allowing for complex configurations that are easily machine-parsable and more expressive than INI files.

Using dictConfig is particularly powerful for defining multiple loggers, handlers, and formatters, linking them together, and setting different propagation rules. Imagine a scenario where you want DEBUG messages from your database module to go to a separate file, INFO messages from all modules to the console, and ERROR messages to be emailed to an operations team – this is easily achievable with a dictionary configuration.

# Example of dictConfig (this would typically be loaded from a YAML/JSON file)

import logging.config

import yaml # Requires PyYAML

logging_config = {

'version': 1,

'disable_existing_loggers': False, # Keep existing loggers intact

'formatters': {

'standard': {

'format': '%(asctime)s [%(levelname)s] %(name)s: %(message)s'

},

'verbose': {

'format': '%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(filename)s:%(lineno)d - %(funcName)s - %(message)s'

}

},

'handlers': {

'console': {

'class': 'logging.StreamHandler',

'formatter': 'standard',

'level': 'INFO'

},

'file_handler': {

'class': 'logging.handlers.RotatingFileHandler',

'formatter': 'verbose',

'filename': 'app_debug.log',

'maxBytes': 10485760, # 10MB

'backupCount': 5,

'level': 'DEBUG'

},

# 'error_email': { # Example for more advanced handlers

# 'class': 'logging.handlers.SMTPHandler',

# 'formatter': 'standard',

# 'level': 'ERROR',

# 'mailhost': ('smtp.example.com', 587),

# 'fromaddr': 'alerts@example.com',

# 'toaddrs': ['ops@example.com'],

# 'subject': 'Application Error Alert!'

# }

},

'loggers': {

'': { # root logger

'handlers': ['console', 'file_handler'],

'level': 'INFO',

'propagate': True

},

'my_application_logger': { # our custom logger from before

'handlers': ['console', 'file_handler'],

'level': 'DEBUG', # Can set a lower level specifically for this logger

'propagate': False # Stop propagation to root for this logger's messages

},

'database_module': { # Example for a specific module's logger

'handlers': ['file_handler'],

'level': 'DEBUG',

'propagate': False

}

}

}

# Load the configuration

# You would typically load this from a .yaml file:

# with open('logging_config.yaml', 'r') as f:

# logging_config = yaml.safe_load(f)

logging.config.dictConfig(logging_config)

logger_app = logging.getLogger("my_application_logger")

logger_db = logging.getLogger("database_module")

logger_app.debug("This app debug message goes to file.") # Debug dont go to console

logger_app.info("This app info message goes to console and file.")

logger_db.debug("This db debug message only goes to file.")

logger_db.info("This db info message goes to file.") # Only file_handler for 'database_module'

Running this code will produce output similar to the following in the console and the app_debug.log file:

Console Output:

2025-06-22 01:20:12,539 [INFO] my_application_logger: This app info message goes to console and file.

app_debug.log content:

2025-06-22 01:20:12,538 - my_application_logger - DEBUG - testing.py:61 - <module> - This app debug message goes to file.

2025-06-22 01:20:12,539 - my_application_logger - INFO - testing.py:62 - <module> - This app info message goes to console and file.

2025-06-22 01:20:12,539 - database_module - DEBUG - testing.py:63 - <module> - This db debug message only goes to file.

2025-06-22 01:20:12,539 - database_module - INFO - testing.py:64 - <module> - This db info message goes to file.

Best Practices for Effective Logging

To fully leverage the logging module, adopt these best practices, especially when developing complex or long-running applications:

- Use Named Loggers: Always obtain a logger with a meaningful name, preferably using

logging.getLogger(__name__). This creates a hierarchical logger structure that mirrors your module structure, making it easy to configure logging for specific parts of your application without affecting others. Avoid using the root logger directly (logging.getLogger()) for your application code, as it can make fine-grained control difficult. - Set Appropriate Levels: Be deliberate about the severity level of each log message.

DEBUGfor internal, detailed flow.INFOfor significant events (startup, user actions).WARNINGfor non-fatal but noteworthy issues.ERRORfor failures of specific operations.CRITICALfor application-impacting failures. This discipline allows for effective filtering in different environments. - Include

exc_info=Truefor Exceptions: When logging an exception that has been caught, always passexc_info=Trueto the logging method (logger.error("Failed to process", exc_info=True)). This automatically includes the full traceback in the log message, which is indispensable for diagnosing runtime errors. - Avoid String Formatting Issues: When logging messages with dynamic data, pass the arguments directly to the logging method instead of pre-formatting the string using f-strings or

.format(). The logging module will only format the string if the message’s level is actually enabled for that handler, saving performance overhead.- Good:

logger.debug("Processing user %s with ID %d", username, user_id) - Bad:

logger.debug(f"Processing user {username} with ID {user_id}")(f-string always evaluates, even if DEBUG is off)

- Good:

- Centralized Configuration: For deployment, always configure logging via

dictConfigorfileConfigfrom an external source. This decouples logging behavior from your code and allows for easy adjustments in different environments (development, staging, production). - Consider Logging to External Services: For distributed systems, integrating handlers that send logs to centralized logging platforms (e.g., ELK Stack, Splunk, cloud logging services) is crucial. This enables aggregation, searching, alerting, and visualization of logs across your entire infrastructure.

- Performance Considerations: While

loggingis efficient, excessiveDEBUG-level logging in performance-critical loops can add overhead. Be mindful of log levels in hot paths. Remember that string formatting only happens if the message passes the level check. - Graceful Shutdown: Ensure that all custom handlers are properly closed on application shutdown to prevent data loss, especially for file-based handlers. The

atexitmodule can be used to register a function to calllogging.shutdown()for this purpose, thoughdictConfighandles this implicitly.

15.2. Runtime Object Introspection: dir(), inspect

Python’s dynamic nature allows for powerful introspection capabilities, enabling developers to examine and manipulate live objects at runtime. This is particularly useful for debugging, testing, and building advanced frameworks or libraries. The built-in dir() function and the inspect module are two primary tools for introspection in Python.

The Built-in dir() Function

The dir() function is a simple yet powerful introspection tool that returns a sorted list of names in the current local scope or the attributes of an object. When called without arguments, it lists the names in the current local scope. When called with an object, it returns the object’s attributes, including methods, properties, and special attributes (those starting with double underscores).

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def my_method(self):

return self.value * 2

# Using dir() to inspect MyClass

print("Attributes of MyClass:")

print(dir(MyClass))

print("\nAttributes of an instance of MyClass:")

instance = MyClass(10)

print(dir(instance))

# Using dir() in a function

def my_function(x, y):

m = x * y

print("\nCalling dir() inside of of my_function:")

print(dir())

return m

print("\nAttributes of my_function:")

print(dir(my_function))

my_function(5, 3)

# Using dir() on a built-in type

print("\nAttributes of the built-in list type:")

print(dir(list))

Executing this code will produce output similar to:

Attributes of MyClass:

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__firstlineno__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__static_attributes__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'my_method']

Attributes of an instance of MyClass:

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__firstlineno__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__static_attributes__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'my_method', 'value']

Attributes of my_function:

['__annotations__', '__builtins__', '__call__', '__class__', '__closure__', '__code__', '__defaults__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__get__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__globals__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__kwdefaults__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__name__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__qualname__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__type_params__']

Calling dir() inside of of my_function:

['m', 'x', 'y']

Attributes of the built-in list type:

['__add__', '__class__', '__class_getitem__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__delitem__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__iadd__', '__imul__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__reversed__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__setitem__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'append', 'clear', 'copy', 'count', 'extend', 'index', 'insert', 'pop', 'remove', 'reverse', 'sort']

The inspect Module

The inspect module is Python’s primary tool for runtime introspection of live objects. It provides functions to examine code, classes, functions, methods, traceback objects, frame objects, and even generator objects. For an expert debugger, inspect is invaluable for understanding the state and definition of code dynamically, without needing to know it ahead of time. It allows you to programmatically access metadata about your running program.

One of the most common uses of inspect is to retrieve information about functions and methods. inspect.signature() returns a Signature object, which provides a rich programmatic representation of the callable’s arguments (parameters, return annotation). This is incredibly useful for validating arguments in frameworks or building API documentation. Similarly, inspect.getsource() can retrieve the source code for a function, class, or module, while inspect.getfile() can tell you where a particular object was defined. This capability is foundational for many IDEs and interactive debugging environments.

import inspect

def my_function(a, b=10, *args, c, **kwargs) -> int:

"""A sample function."""

pass

class MyClass:

def my_method(self, x: float) -> None:

pass

# Get function signature

sig = inspect.signature(my_function)

print(f"Function signature: {sig}")

for param in sig.parameters.values():

print(f" Parameter: {param.name}, Kind: {param.kind}, Default: {param.default}")

# Get source code

try:

print("\nSource code of my_function:\n" + inspect.getsource(my_function))

except TypeError:

print("\nCould not get source for my_function (e.g., if defined interactively).")

# Get members of a class

print("Members of MyClass:")

for name, member in inspect.getmembers(MyClass):

if not name.startswith("__"):

print(f" {name}: {inspect.signature(member)}")

The output of this code will look like:

Function signature: (a, b=10, *args, c, **kwargs) -> int

Parameter: a, Kind: POSITIONAL_OR_KEYWORD, Default: <class 'inspect._empty'>

Parameter: b, Kind: POSITIONAL_OR_KEYWORD, Default: 10

Parameter: args, Kind: VAR_POSITIONAL, Default: <class 'inspect._empty'>

Parameter: c, Kind: KEYWORD_ONLY, Default: <class 'inspect._empty'>

Parameter: kwargs, Kind: VAR_KEYWORD, Default: <class 'inspect._empty'>

Source code of my_function:

def my_function(a, b=10, *args, c, **kwargs) -> int:

"""A sample function."""

pass

Members of MyClass:

my_method: (self, x: float) -> None

Beyond functions, inspect allows deeper introspection into object attributes using inspect.getmembers() and property hierarchies with inspect.getmro() for classes. It can also distinguish between different types of callables (functions, methods, built-ins) using inspect.isfunction(), inspect.ismethod(), etc. For live objects, inspect.getmodule() identifies the module an object belongs to, and inspect.getcomments() can even retrieve comment strings. This comprehensive suite of tools makes inspect indispensable for dynamic analysis, automated testing, and crafting sophisticated metaprogramming solutions.

15.3. Runtime Stack Frame Introspection

At the heart of Python’s execution model is the call stack, a series of frame objects. Each time a function is called, a new frame object is pushed onto the stack. This frame object holds crucial runtime information: local variables, the code object being executed, the current instruction pointer (bytecode offset), the previous frame in the call stack, and more. Python’s introspection capabilities extend to these live frame objects, allowing for powerful, albeit cautious, runtime analysis and debugging.

The primary, low-level way to access frame objects is through sys._getframe(). This function (note the leading underscore, indicating it’s not part of the public API but widely used by debuggers) returns the current frame object or a frame object higher up the call stack. For example, sys._getframe(0) gets the current frame, sys._getframe(1) gets the caller’s frame, and so on. Once you have a frame object, you can access its attributes like f_locals (a dictionary of local variables), f_globals (a dictionary of global variables), f_code (the code object being executed in this frame), f_lasti (the last instruction index executed), and f_back (the previous frame in the stack).

import sys

def outer_func():

x = 10

print(f"Inside {outer_func.__name__}: {x=}")

inner_func()

print(f"After inner_func call: {x=}")

def inner_func():

y = 20

frame = sys._getframe(0) # Get current frame

print(f"Inside {frame.f_code.co_name}:")

print(f" Local variables: {frame.f_locals}")

print(f" Code object name: {frame.f_code.co_name}")

caller_frame = frame.f_back # Get caller's frame

if caller_frame:

print(f" Caller function: {caller_frame.f_code.co_name}")

print(f" Caller's locals: {caller_frame.f_locals}")

# Modifying a caller's local variable (highly discouraged in production!)

caller_frame.f_locals["x"] = 99

print(f" Caller's 'x' modified to: {caller_frame.f_locals['x']}")

outer_func()

This code demonstrates how to access and manipulate frame objects:

Inside outer_func: x=10

Inside inner_func:

Local variables: {'y': 20, 'frame': <frame at 0x0000020CCAFF02E0, file '/path/to/module.py', line 15, code inner_func>}

Code object name: inner_func

Caller function: outer_func

Caller's locals: {'x': 10}

Caller's 'x' modified to: 99

After inner_func call: x=99

While sys._getframe() and direct frame attribute access offer immense power for debugging and dynamic analysis (e.g., custom debuggers or profilers that need to inspect arbitrary points in the call stack), direct modification of f_locals or f_globals is generally discouraged in production code. Such modifications can lead to unexpected behavior and are primarily for advanced debugging tools. For higher-level inspection, inspect.currentframe() and inspect.stack() provide more convenient and safer ways to navigate the call stack.

15.4. Interpreter Profiling Hooks

Python provides low-level hooks into its interpreter’s execution flow, enabling powerful line-level introspection and custom profiling. These hooks are set using sys.settrace() and sys.setprofile(), which allow you to register callback functions that are invoked at specific points during code execution.

sys.settrace(func): This function registers a trace function (func). The trace function is called for every “event” that occurs during program execution. These events include:

'call': A function is entered.'line': A line of code is about to be executed.'return': A function is about to return.'exception': An exception has occurred.'opcode': (Python 3.11+) An opcode is about to be executed.

The trace function receives three arguments: frame (the current stack frame), event (the event type string), and arg (event-specific argument, e.g., the return value or exception info). By inspecting the frame object and the event type, you can implement custom debuggers, code coverage tools, or sophisticated logging mechanisms. Because the trace function is called for every event, it introduces significant overhead and should be used judiciously.

import sys

def my_trace_function(frame, event, arg):

# Filter for specific events or code paths

if event == 'line' and 'my_trace_function' not in frame.f_code.co_name:

co = frame.f_code

lineno = frame.f_lineno

print(f"TRACE: {co.co_filename}:{lineno} - {co.co_name}()")

return my_trace_function # Must return itself to continue tracing

def example_function(a, b):

result = a + b # line 12

return result # line 13

sys.settrace(my_trace_function)

print("Starting traced execution...")

example_function(5, 3)

print("Finished traced execution.")

sys.settrace(None) # Disable tracing

This code sets up a trace function that prints the filename, line number, and function name for every line executed by python (except for the trace function itself). The output will look like this:

# Starting traced execution...

# TRACE: /path/to/module.py:12 - example_function()

# TRACE: /path/to/module.py:13 - example_function()

# Finished traced execution.

sys.setprofile(func): Similar to settrace(), setprofile() registers a profile function (func). However, the profile function is called only for 'call', 'return', and 'exception' events, making it less granular than settrace(). This reduced granularity means setprofile() incurs less overhead, making it more suitable for profiling tools that need function-level timings rather than line-level execution details. Python’s built-in cProfile module is implemented using this hook for its efficiency. Both settrace() and setprofile() are powerful tools for deep code instrumentation but require careful design to avoid performance degradation.

15.5. C-Level Debugging