Part II: Types, Memory, and Core Language Internals

Part II of the C# Mastery Guide delves into the core types and memory management principles that underpin C# programming. This section provides a deep understanding of how types are defined, how memory is managed, and the intricacies of the Common Type System (CTS) and the Common Language Runtime (CLR).

Table of Contents

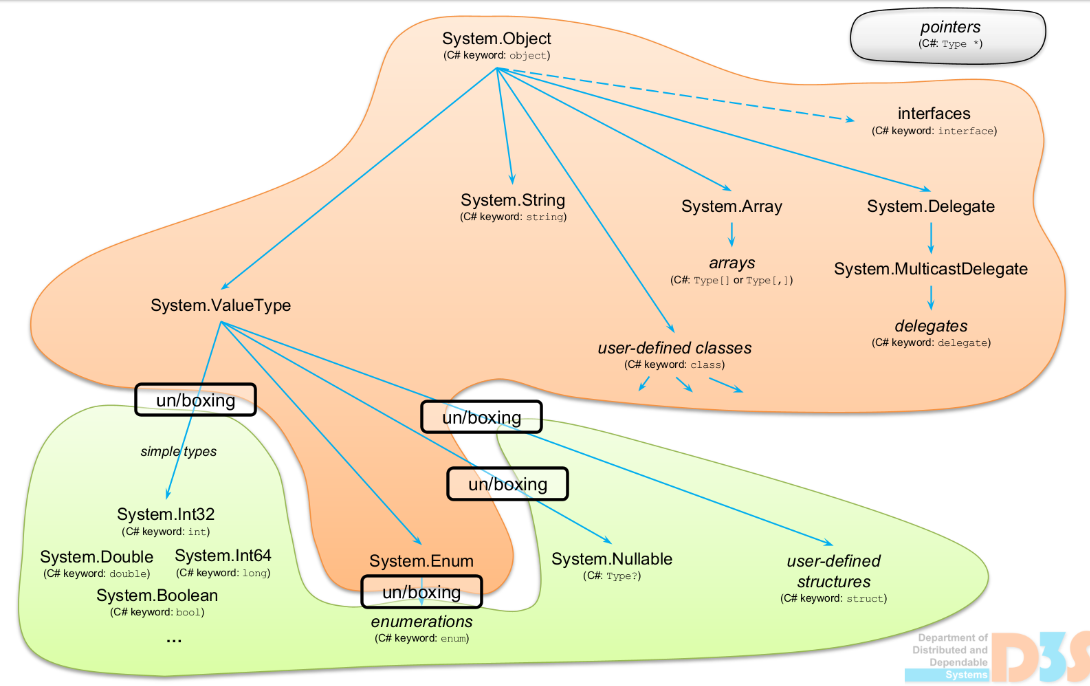

3. The Common Type System (CTS): Values, References, and Memory Layout

- 3.1. The Stack and the Heap: A definitive guide to where your data lives. Exploring method calls, stack frames, and object allocation strategies.

- 3.2. The Great Unification:

System.Object: Understanding the ultimate base type for all C# types and the foundational role of type metadata and the Method Table. - 3.3. Value Types (

struct): In-depth analysis of their memory layout, whySystem.ValueTypeexists, storage implications on the stack or inline within objects, performance characteristics, and the Method Table’s role for unboxed instances. - 3.4. Reference Types (

class): Understanding object headers (Method Table Pointer, Sync Block Index), how object references are stored, the detailed contents of the Method Table, and its relationship toSystem.Typeand reflection. - 3.5. Boxing and Unboxing: How value types are converted to objects (boxing), the associated significant performance costs, and strategies to avoid it.

- 3.6. Scope and Lifetime: Differentiating lexical scope in C# (compile-time visibility) from object lifetime managed by the Garbage Collector (runtime memory management).

- 3.7. Default Values and the

defaultKeyword: Understanding the default initialization values for built-in types (e.g.,intto0,booltofalse, reference types tonull), and thedefaultkeyword for obtaining these values for any type.

4. Memory Management and Garbage Collection

- 4.1. The .NET Generational Garbage Collector: How the tracing GC works. Detailed explanation of Generations 0, 1, and 2, and the mark-and-compact algorithm.

- 4.2. The Large Object Heap (LOH): Understanding why large objects (arrays, strings) are treated differently, their allocation patterns, and the problem of fragmentation on the LOH.

- 4.3. Finalization and

IDisposable: TheDisposepattern for deterministic cleanup of unmanaged resources vs. non-deterministic finalizers. Coversusingstatements,usingdeclarations (C# 8), andawait usingforIAsyncDisposable(C# 8). - 4.4. Weak References: Using

WeakReference<T>for scenarios like caching, preventing strong references from hindering garbage collection, and avoiding memory leaks. - 4.5. Advanced GC: Deep dive into Workstation vs. Server GC modes, concurrent collection, and tuning the GC behavior with

GCSettingsfor specific application needs.

5. Assemblies, Type Loading, and Metadata

- 5.1. Assembly Loading: How the CLR resolves, locates, and loads assemblies during runtime, including the role of

AssemblyLoadContextfor isolation. - 5.2. Organizing Code: Namespaces, File-Scoped Namespaces (C# 10), and Global Usings (C# 10): How namespaces function as a compile-time construct, the benefits of file-scoped namespaces for conciseness, and the impact of global usings on project-wide imports.

- 5.3. Reflection and Metadata: Reading and manipulating type information at runtime using

System.Reflection. Understanding the performance cost and the immense power of late binding. - 5.4. Dynamic Code Generation with

System.Reflection.Emit: Emitting Common Intermediate Language (IL) at runtime to dynamically create types, methods, and assemblies. - 5.5. Runtime Type Handles and Type Identity: Understanding the internal representation and significance of

RuntimeTypeHandle,RuntimeMethodHandle, andRuntimeFieldHandlefor unique type and member identification. - 5.6. Attributes: Metadata for Control and Information: Common Usage and Core Behaviors: A deep dive into frequently used built-in attributes (e.g.,

[Obsolete],[Serializable],[Conditional],[MethodImpl],[DllImport]), explaining their purpose and how they influence the compiler, runtime, or external tools. - 5.7. Custom Attributes: Definition, Usage, and Reflection: How attributes are defined, applied to code elements, processed at compile-time by tools, and discovered/interpreted at runtime via reflection.

6. Access Modifiers: Visibility, Encapsulation, and Advanced Scenarios

- 6.1. Fundamental Modifiers (

public,private): Their basic scope and usage within a type and within a project. - 6.2. Assembly-level Modifiers (

internal,fileC# 11): Controlling visibility across assembly boundaries, including theInternalsVisibleToattribute for controlled internal exposure. - 6.3. Inheritance-based Modifiers (

protected,private protectedC# 7.2,protected internal): Nuances of access within class hierarchies, and the precise distinctions betweenprivate protected(accessible only within derived types in the same assembly) andprotected internal(accessible within derived types in any assembly, or any type in the same assembly). - 6.4. Default Access Levels: What default access is applied to types and members if no modifier is explicitly specified.

3. The Common Type System (CTS): Values, References, and Memory Layout

At the heart of the .NET ecosystem lies the Common Type System (CTS). The CTS is a fundamental specification that defines how types are declared, used, and managed in the .NET runtime, ensuring that types written in different .NET languages can interact seamlessly. A deep understanding of the CTS, particularly the distinction between value types and reference types and their respective memory layouts, is paramount for writing high-performance, robust, and idiomatic C# code. This chapter will take you on a detailed tour of where your data resides and how the runtime manages it.

3.1. The Stack and the Heap

Before delving into specific type categories, it’s essential to understand the two primary memory regions managed by the Common Language Runtime (CLR) where your application’s data lives: the Stack and the Heap.

The Stack

The stack is a contiguous block of memory that operates on a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) principle. It’s primarily used for:

- Method Calls (Stack Frames): When a method is called, a new stack frame is pushed onto the stack. This frame contains:

- The return address (where to resume execution after the method completes).

- The method’s arguments.

- Local variables declared within the method.

- Value Type Storage: Instances of value types (like

int,bool,structs) declared as local variables or method parameters are stored directly on the stack. - Reference Storage: For reference types, the reference (memory address) to the object on the heap is stored on the stack as a local variable or method argument.

Characteristics of the Stack:

- Extremely Fast: Allocation and deallocation are incredibly quick, involving only moving a pointer (the stack pointer).

- Automatic Management: Memory is automatically reclaimed when a method returns (the stack frame is popped). This makes stack-based allocations very efficient and predictable.

- Limited Size: The stack has a relatively small, fixed size (typically 1MB or a few MBs, depending on configuration and OS), making it unsuitable for large or long-lived data.

- Thread-Specific: Each thread in a .NET process has its own separate stack.

Diagram of the stack during method calls:

ʌ Stack Grows Upwards (towards lower addresses)

|

+--------------------------+

| MethodC's Stack Frame | <-- Stack Pointer

| - LocalVarC |

| - ArgC |

| - ReturnAddress_B |

+--------------------------+

| MethodB's Stack Frame |

| - LocalVarB |

| - ArgB |

| - ReturnAddress_A |

+-------------------------=+

| MethodA's Stack Frame |

| - LocalVarA |

| - ArgA |

| - ReturnAddress_Main |

+--------------------------+

| Main Method's Stack Frame|

| - ... |

+--------------------------+

When MethodC completes, its stack frame is popped, and the memory becomes immediately available for the next method call.

The Heap

The heap is a much larger pool of memory used for dynamic memory allocation. It’s where instances of reference types (like classes, strings, objects, arrays) are stored.

Characteristics of the Heap:

- Dynamic Allocation: Memory is allocated on demand using the

newoperator. The CLR finds a suitable block of memory on the heap. - Slower Allocation: Compared to the stack, allocating on the heap is slower because the runtime needs to find free memory blocks and manage them.

- Garbage Collected: Memory on the heap is automatically managed by the .NET Garbage Collector (GC). Objects remain on the heap as long as there are references to them. Once an object is no longer referenced, it becomes eligible for collection, and the GC will eventually reclaim its memory. This “automatic” management simplifies development but introduces non-deterministic deallocation.

- Global Access (within process): Heap objects can be accessed from anywhere in the application as long as a valid reference exists.

- Larger Size: The heap can grow and shrink dynamically as needed, limited only by available system memory.

Diagram showing stack and heap interaction:

+---------------------------+ +-------------------------------------------+

| Stack | | Heap |

+---------------------------+ +-------------------------------------------+

| main() frame | | Object A (e.g., MyClass instance) |

| - MyClass objRef | ---> | [Address of MyClass instance] |

| - int x = 10; | | Array item values |

| - int[] arr = new int[5] | ---> | [Address of the array values] |

+---------------------------+ +-------------------------------------------+

In this diagram, x (a value type) lives directly on the stack. objRef (a reference type variable) also lives on the stack, but its value is a memory address pointing to the actual MyClass instance, which lives on the heap. The arr array itself is allocated on the heap, but the arr variable lives on the stack and holds a reference to the array’s memory address.

3.2. The Great Unification: System.Object

At the very top of the .NET type hierarchy resides System.Object. This class is the ultimate base type for every other type in the Common Type System (CTS), regardless of whether it’s a value type or a reference type. This “great unification” is fundamental to .NET’s power, enabling polymorphism, reflection, and cross-language interoperability.

Polymorphism is a core concept in object-oriented programming that allows objects of different types to be treated through a common interface, enabling the same operation or method call to behave differently depending on the actual type of the object at runtime. C# achieves this via inheritances, abstract classes and virtual methods.

The Root of All Types

Because all types implicitly or explicitly derive from System.Object, you can treat any instance of any type as an object. This allows for highly flexible code, enabling you to write methods that operate on generic object instances or to store diverse types in collections of object.

object obj1 = 10; // An int (value type) boxed to object

object obj2 = "Hello"; // A string (reference type)

object obj3 = new MyClass(); // A custom class (reference type)

List<object> mixedList = new List<object> { obj1, obj2, obj3 };

// All can be treated uniformly as objects

For more details on System.Object, consult the official System.Object Class documentation on Microsoft Learn.

System.Object Methods

System.Object defines a small set of fundamental instance methods that all derived types inherit and can override. These methods include:

public virtual bool Equals(object obj): Determines whether the specified object is equal to the current object. By default, for reference types, this performs a reference equality check (do both variables point to the exact same object in memory). For value types, the defaultSystem.ValueType.Equalsimplementation performs a field-by-field comparison (though this can be inefficient via reflection).Object.Finalize(): Special method declared as~MyClass() { ... }in C#, which is called by the garbage collector before reclaiming the object’s memory. This finalizer method is used to release unmanaged resources. However, it is generally recommended to implement theIDisposableinterface and use theDisposepattern for deterministic cleanup instead of relying on finalizers.public virtual int GetHashCode(): Serves as a hash function for a particular type. It’s crucial for types used as keys in hash-based collections (Dictionary<TKey, TValue>,HashSet<T>). The default implementation typically returns a hash based on the object’s reference (for reference types) or a reflection-based hash for value types.public Type GetType(): Returns the exact runtimeSystem.Typeof the current instance. This method issealed, meaning it cannot be overridden.protected object MemberwiseClone(): Creates a shallow copy of the current object by copying the nonstatic field values (including private fields). This is useful for implementing cloning behavior in derived classes.public static bool ReferenceEquals(object objA, object objB): Determines whether the specifiedObjectinstances are the same instance in memory.public virtual string ToString(): Returns a string that represents the current object. The default implementation typically returns the fully qualified name of the type (e.g., “MyNamespace.MyClass”).

The Equals, GetHashCode and ToString methods are virtual precisely because their behavior often needs to be specialized by derived types to provide meaningful semantics (e.g., custom value equality, useful string representations).

Type Metadata and the Method Table (MT)

At the heart of the CLR’s understanding of types lies type metadata. Every single type definition in a .NET application — be it a class, struct, enum, interface, or delegate ─ has associated static metadata. This metadata is the CLR’s comprehensive blueprint for that type.

This metadata is primarily organized and managed internally by a structure conceptually referred to as the Method Table (MT). While the exact internal implementation name might vary (e.g., EEClass in some CLR versions), the concept remains consistent: it’s a static, per-type data structure that defines everything the CLR needs to know about a type at runtime.

- Universal Presence: It’s crucial to grasp that a Method Table exists for every type definition. This is not exclusive to classes or objects on the heap. Even a simple

intor a customstructhas an associated Method Table defining its characteristics.

Contents of the Method Table

The Method Table itself is a static, per-type data structure that serves as the CLR’s comprehensive blueprint for a type. It contains:

- Pointers to JIT-compiled native code for all type methods: Includes both instance and static methods as well as the crucial Virtual Method Table (V-Table), which is an array of function pointers specifically for virtual methods defined in the type or its base classes. When a virtual method is called on an object, the CLR uses the MT pointer to find the V-Table, then the appropriate entry for the method based on the object’s actual runtime type, enabling polymorphism.

- Type identity information: The type’s full name, a pointer to its base type’s Method Table, and a list of all interfaces it implements. This allows the CLR to perform

isandaschecks at runtime. - Object layout information: The total size of the object in memory (excluding the header), and the offsets of its instance fields within the object. This tells the CLR how to interpret the bytes following the header as the object’s data.

- Pointers to the locations of static fields: Static fields are stored once per type, not per instance, and the MT points to where this static data resides.

- Various flags and other metadata: Used by the CLR for internal runtime checks, security validations, and optimizations.

Connection to System.Type and Reflection

The CLR leverages these low-level metadata structures, particularly the Method Table, to construct and manage System.Type objects. When you use typeof(MyClass) or myInstance.GetType(), the CLR internally consults the relevant Method Table (or its internal representation, a TypeHandle) to retrieve or (lazily) create a System.Type object. This System.Type object is the managed API representation of a type’s metadata, providing the rich information that powers reflection (e.g., allowing you to enumerate methods, properties, fields, or even create instances at runtime, as discussed in Chapter 5).

The CTS’s reliance on System.Object as the universal root and the consistent use of Method Tables for all types are key enablers for .NET’s powerful features like garbage collection, type safety, and language interoperability.

3.3. Value Types (struct)

Value types directly contain their data. In C#, structs, enums, and all primitive types (like int, double, bool, char) are value types. They implicitly inherit from System.ValueType, which itself inherits from System.Object.

For more details on value types, consult the official Value Types documentation on Microsoft Learn.

Why System.ValueType Exists

System.ValueType serves several critical roles in the CTS:

- Semantic Marker: It acts as a base class that all value types implicitly inherit from, explicitly signaling to the CLR and the C# compiler their unique memory semantics (copy-by-value, direct data storage). This is how the runtime distinguishes between types that should reside on the stack/inline versus those that require heap allocation.

-

Consistent Base for Overrides: Although

System.ValueTypedoesn’t add any new members beyondSystem.Object, it provides crucial overrides forEquals()andGetHashCode():- The default

System.ValueType.Equals()provides value-based equality by performing a field-by-field (including private fields) comparison using reflection. - Similarly,

GetHashCode()provides a hash based on the field values, again using reflection.

While these default implementations are often inefficient (due to reflection and boxing),

System.ValueType’s existence ensures that all value types conceptually align with theSystem.Objecthierarchy while having distinct default behaviors for these crucial methods, encouraging developers to override them for performance. - The default

Memory Layout and Storage

The key characteristic of value types is where their data is stored, which is always directly embedded:

-

On the Stack: When a value type is declared as a local variable within a method or passed as a method parameter (by value, which is the default for value types), its entire data is allocated directly on the stack, within the current method’s stack frame.

struct Point { public int X; public int Y; } void CalculateDistance() { Point p1 = new Point { X = 10, Y = 20 }; // p1's data (X, Y) is on the stack int radius = 5; // radius's data (5) is on the stack // ... } // When CalculateDistance exits, p1 and radius are deallocated instantly. -

Inline within Reference Types (on the Heap): When a value type is a field of a reference type (a

class), its data is stored inline directly within the memory allocated for that reference type object on the heap. Crucially, no separate heap allocation occurs for the value type itself.class Circle { public Point Center; // Center (a Point struct) is stored directly within the Circle object on the heap public double Radius; } void CreateCircle() { Circle c = new Circle { Center = new Point { X = 0, Y = 0 }, Radius = 5.0 }; // The 'c' variable (reference) is on the stack. // The Circle object (including its Center and Radius data) is a single allocation on the heap. }In this scenario,

Point’sXandYdata do not cause a separate heap allocation; they are contiguous within theCircleobject’s memory block.

The Method Table and Value Type Instances (Deeper Dive)

As discussed, every C# type definition has a Method Table. This holds true for structs as well. The Method Table for Point (in our example) would contain information about its fields (X, Y), its default constructor, any custom methods (ToString(), Equals(), etc.), and its base type (System.ValueType).

However, and this is a critical distinction, instances of value types (when not boxed) do not contain a direct pointer to their Method Table in their memory layout.

Why? (A Core Design Choice for Efficiency): This design decision is a direct consequence of value types’ fundamental characteristics in C#:

- No Inheritance: Structs cannot serve as base classes for other classes or structs. They can only implement interfaces.

- No Virtual Methods: All methods defined on a

struct(or inherited fromSystem.ObjectandSystem.ValueType) are implicitlysealedand non-virtual.

Because of these restrictions, the exact type of a struct instance and the specific implementation of its methods are definitively known at compile time. This allows the JIT compiler to directly resolve method calls (e.g., p1.ToString()) or even inline the method code, without needing a runtime lookup via a Method Table pointer stored in each instance. Eliminating this pointer (typically 8 bytes on a 64-bit system) for every instance significantly saves memory, especially when many small structs are used.

Copy Semantics

This is the most fundamental operational difference between value types and reference types:

-

When a value type instance is assigned to another variable, passed as an argument to a method (by value, which is the default), or returned from a method, a complete bitwise copy of its entire data is made. The two variables then hold independent copies of the data.

Point p1 = new Point { X = 10, Y = 20 }; Point p2 = p1; // p2 is a *new, independent copy* of p1. p2.X = 100; // Changes p2.X, but p1.X remains 10. Console.WriteLine($"p1: ({p1.X}, {p1.Y})"); // Output: p1: (10, 20) Console.WriteLine($"p2: ({p2.X}, {p2.Y})"); // Output: p2: (100, 20)This behavior implies that modifying one variable will not affect the other, which can be desirable for immutability or isolated operations.

The new Operator for Structs

When new is used with a struct (e.g., new Point()), it calls the struct’s constructor (or the implicit parameterless constructor) and initializes the memory allocated for the struct. Crucially, this operation does not cause a heap allocation for the struct instance itself. The memory is initialized either on the stack (for local variables) or inline on the heap (if the struct is a field of a class).

Performance Characteristics

- Fast Allocation/Deallocation: When allocated on the stack, value types offer superior performance due to the trivial nature of stack pointer manipulation.

- Reduced Garbage Collection Overhead: Since unboxed value types are stored on the stack or inlined on the heap, they are not individual objects managed by the GC. This significantly reduces GC pressure, leading to fewer and shorter GC pauses.

- Memory Locality: Data for value types is often stored contiguously in memory, which can improve CPU cache performance by reducing cache misses.

- Default

ValueTypeMethods: The default implementations ofEquals()andGetHashCode()can be inefficient due to reflection. Therefore, it’s often beneficial to override these methods in your structs for performance-critical applications. - Copy Cost Trade-off: For very large

structs (e.g., structs with many fields or large fields), the cost of copying the entire data on assignment or method calls can become substantial, potentially degrading performance. In such cases, passing thestructby reference using theinmodifier (C# 7.2+) can mitigate this copy cost:void ProcessPoint(in Point p) // p is passed by reference, cannot be modified { Console.WriteLine($"Processing point: ({p.X}, {p.Y})"); // p.X = 5; // Compile-time error: Cannot modify members of 'p' because it is an 'in' parameter } ref structandscoped ref(Advanced): C# 7.2 introducedref struct(e.g.,Span<T>,ReadOnlySpan<T>) which are strictly stack-allocated and cannot escape the stack, preventing accidental heap allocation and enabling powerful, high-performance memory manipulation. C# 11 addedscoped refparameters to further enforce safe usage ofreflocals andrefparameters. These features offer extreme performance by ensuring stack-only semantics.

Default struct Constructor

All structs implicitly have a public parameterless constructor that initializes all fields to their default values ━ e.g., 0 for numeric fields, false for bool, null for reference-type fields within the struct, and recursively default-initializes any nested structs.

3.4. Reference Types (class)

Reference types store a reference (a memory address) to the actual data, which resides on the managed heap. In C#, classes, interfaces, delegates, arrays, and strings are reference types. They all implicitly or explicitly inherit from System.Object.

For more details on reference types, consult the official Reference Types documentation on Microsoft Learn.

Memory Layout and Storage

- Always on the Heap: Instances of reference types are always allocated on the managed heap using the

newoperator. There is no concept of a reference type instance existing on the stack directly (only its reference might be on the stack). -

References on Stack or Heap: A variable declared as a reference type doesn’t contain the object itself; it contains a reference (a memory address or pointer) to the object’s location on the heap. This reference can be stored:

- On the stack (if it’s a local variable or method parameter).

- On the heap (if it’s a field of another reference type object).

class Customer { public string Name; public int Id; } void CreateCustomer() { Customer customer1 = new Customer { Name = "Alice", Id = 101 }; // The 'customer1' variable (reference) is on the stack. // The Customer object data ("Alice", 101) is on the heap. }

Object Header: Deep Dive

Every object allocated on the managed heap (instances of reference types, including boxed value types) incurs a small amount of overhead for the object header. This header, typically 16-24 bytes on 64-bit systems (due to factors like compressed pointers, which are often enabled by default), contains crucial information for the CLR to manage the object. The two primary components of the object header are:

1. Method Table Pointer (MT)

- Crucial Difference: Unlike unboxed value type instances, every instance of a reference type on the heap contains a direct pointer to its type’s Method Table in its object header. This pointer is fundamental for the CLR to understand the object at runtime.

- Purpose of the Method Table Pointer:

- Virtual Method Dispatch: When a virtual method is called on an object, the CLR uses this pointer to look up the Method Table, which contains the V-Table for virtual methods. This allows the CLR to resolve the correct method implementation based on the actual runtime type of the object, enabling polymorphism.

- Type Identity: The Method Table Pointer also serves as a quick way to determine the exact type of an object at runtime, facilitating operations like

is,as, and reflection.

2. Sync Block Index (SBI)

- An index into a table of synchronization blocks (managed internally by the CLR). This part of the header is used for various runtime services:

- Object Locking: When using

lockstatements orMonitorclass methods for thread synchronization, the SBI points to the entry in the Sync Block table that manages the lock for this specific object. - Object Hashing: If

GetHashCode()is called on an object and it hasn’t been overridden to return a custom hash, the default implementation often stores a hash code generated from the object’s memory address in the Sync Block entry. - Weak References: Used internally by the GC for managing weak references to the object (further discussed in Chapter 4).

- Object Locking: When using

Diagram of an object on the heap:

+-----------------------------------+ \

| Method Table Pointer (MT) | |

|-----------------------------------| | Object Header (16-24 bytes)

| Sync Block Index (SBI) | /

+===================================+ \

| Field1 (e.g., Customer.Name) | |

|-----------------------------------| |

| Field2 (e.g., Customer.Id) | | Instance Data (variable size)

|-----------------------------------| |

| ... | |

+-----------------------------------+ /

Reference Semantics

-

When a reference type variable is assigned to another, passed as an argument, or returned from a method, only the reference (memory address) is copied, not the object’s data. Both variables will then point to the exact same object instance in memory.

Customer customer1 = new Customer { Name = "Alice", Id = 101 }; Customer customer2 = customer1; // customer2 now refers to the *same object* as customer1. customer2.Id = 102; // Changes the Id of the *single* object referenced by both. Console.WriteLine($"customer1's Id: {customer1.Id}"); // Output: 102 Console.WriteLine($"customer2's Id: {customer2.Id}"); // Output: 102This behavior enables shared state and is fundamental to object-oriented programming paradigms, but it also means that modifications through one reference are visible through all others.

string as a Special Reference Type

While string (System.String) is a class and thus a reference type, it exhibits some special behaviors that differentiate it from typical reference types:

- Immutability: Once a

stringobject is created, its content cannot be changed. Any operation that appears to modify a string (e.g.,string.Replace(),string.ToUpper()) actually creates a newstringobject and returns it. This immutability makes strings thread-safe and predictable. - String Interning: For efficiency, the CLR performs string interning for literal strings. If the same string literal appears multiple times in your code, the CLR might store only one copy of that string in a special pool (the “intern pool”), and all references to that literal will point to the same object. This can lead to

==(value equality) andReferenceEquals()(reference equality) both returningtruefor identical string literals.

string s1 = "Hello";

string s2 = "Hello";

string s3 = new StringBuilder().Append("He").Append("llo").ToString();

Console.WriteLine(s1 == s2); // True (value equality)

Console.WriteLine(object.ReferenceEquals(s1, s2)); // True (due to interning of literals)

Console.WriteLine(s1 == s3); // True (value equality)

Console.WriteLine(object.ReferenceEquals(s1, s3)); // False (s3 is a new object from StringBuilder)

Reference Type Performance Considerations

- Heap Allocation Cost: Allocating objects on the heap is slower than stack allocation and involves the CLR’s memory manager searching for free blocks.

- Garbage Collection Pressure: Every object on the heap contributes to the workload of the Garbage Collector. Creating many short-lived objects on the heap can increase GC frequency and duration, potentially leading to performance pauses in your application.

3.5. Boxing and Unboxing

The unification of all types under System.Object is powerful, but it comes with a performance cost when dealing with value types. Boxing is the process that allows a value type instance to be treated as an System.Object instance (or an interface type it implements). Unboxing is the reverse.

For more details on boxing value types, see the official documentation.

The Boxing Process

Boxing involves transforming a value type from its stack-allocated or inline-on-heap representation into a full-fledged object on the managed heap. This process is expensive because it involves several steps:

- Heap Allocation: A new object is allocated on the managed heap. The size of this allocated object is sufficient to hold the value type’s data plus the standard object header (which includes a Method Table Pointer and a Sync Block Index for this newly boxed type).

- Data Copy: The actual data of the value type is copied from its original location (stack or inline in another object) into this newly allocated heap object.

- Reference Return: A reference (memory address) to this new heap object is returned. This reference is then stored in the

objectvariable.

int myInt = 42; // myInt is a value type, typically on the stack

object boxedInt = myInt; // BOXING occurs here

// Console.WriteLine(myInt == boxedInt); // Compile-time error:

// Operator '==' cannot be applied to operands of type 'int' and 'object'

Console.WriteLine($"Boxed int value: {boxedInt}");

Console.WriteLine($"Boxed int type: {boxedInt.GetType().Name}");

// Output:

// Boxed int value: 42

// Boxed int type: Int32

The Unboxing Process

Unboxing is the process of extracting the value type data from a previously boxed object.

- Type Check: The CLR first performs a runtime type check to ensure that the object reference being unboxed is indeed a boxed instance of the target value type. If the types don’t match (e.g., trying to unbox a boxed

intto adouble), anInvalidCastExceptionis thrown. - Data Copy: The data from the heap-allocated boxed object is copied back to a location suitable for the value type (e.g., a local variable on the stack or a field).

object boxedValue = 123; // Already boxed

int unboxedValue = (int)boxedValue; // UNBOXING occurs here

Console.WriteLine($"Unboxed value: {unboxedValue}"); // Output: 123

Significant Performance Implications

Boxing and unboxing are considered expensive operations and represent a common performance pitfall in .NET applications, especially in hot code paths or tight loops.

- Heap Allocation Overhead: Boxing necessitates allocating memory on the managed heap, which is significantly slower than stack allocation and contributes to memory fragmentation.

- Data Copying Overhead: Data is copied at least twice: once during boxing (from source to heap) and potentially again during unboxing (from heap to target).

- Garbage Collection Pressure: Each boxed object is a distinct new object on the heap, increasing the number of objects the Garbage Collector needs to track and manage. Frequent boxing can lead to more frequent and longer GC pauses, impacting application responsiveness.

When Boxing to object Occurs

Boxing can happen implicitly or explicitly:

- Implicit Boxing:

- Passing value types to

objectparameters:void PrintObject(object obj) => Console.WriteLine(obj); int number = 100; PrintObject(number); // 'number' is implicitly boxed to object. - Adding value types to non-generic collections:

System.Collections.ArrayList myArrayList = new System.Collections.ArrayList(); myArrayList.Add(5); // int 5 is boxed myArrayList.Add(true); // bool true is boxed - Using

string.Format()orConsole.WriteLine()with value types: (Often optimized by compiler/runtime, but conceptual boxing can occur in older versions or for arbitraryobjectarguments).Console.WriteLine("Value: {0}", 123); // 123 is boxed to object to fit the {0} placeholder.

- Passing value types to

- Explicit Boxing (Casting):

int x = 10; object y = (object)x; // Explicit cast to object, causes boxing.

Boxing to Interface Types

When a value type implements an interface, boxing occurs when the value type is assigned to an interface type variable. This allows the value type to be treated as an instance of the interface.

interface IPrintable { void Print(); }

struct Point : IPrintable

{

public void Print() => Console.WriteLine("Point");

}

class Printer

{

public static void PrintItem(IPrintable item) => item.Print();

}

Point point = new Point();

Printer.PrintItem(point); // Boxing occurs here, Point is boxed to IPrintable

This can however be prevented by using generic interfaces or methods, which allow you to work with value types without boxing.

interface IPrintable<T> { void Print(); }

struct Point : IPrintable<Point>

{

public void Print() => Console.WriteLine("Point");

}

class Printer

{

public static void PrintItem<T>(IPrintable<T> item) => item.Print();

}

Point point = new Point();

Printer.PrintItem(point);

No boxing occurs here because the method PrintItem<T> is generic and operates on IPrintable<T>, where T is the concrete type of the value being passed. The Point struct implements IPrintable<Point>, so the interface is closed over the value type itself. This allows the JIT to generate specialized, type-safe code that avoids boxing, since it can directly work with the value type without converting it to an object or reference type.

Value Types and Object.ReferenceEquals(object objA, object objB)

When comparing value types. If objA and objB are value types, they are boxed before they are passed to the ReferenceEquals method. This means that if both objA and objB represent the same instance of a value type, the ReferenceEquals method nevertheless returns false, as the following example shows.

int int1 = 3;

Console.WriteLine(Object.ReferenceEquals(int1, int1));

// Output: False (because int1 is boxed twice, creating two separate heap objects)

Strategies to Avoid Boxing

Avoiding boxing, especially in performance-critical sections of your code, is crucial for high-performance .NET development:

- Use Generics (

List<T>,Dictionary<TKey, TValue>, etc.): This is the most common and effective solution. Generics allow you to write type-safe code that works with value types (and reference types) without involvingSystem.Object, thus eliminating boxing.List<int> myIntList = new List<int>(); myIntList.Add(5); // No boxing int item = myIntList[0]; // No unboxing - Use Generic Interfaces: If you need to work with interfaces and boxing is an issue, define them as generic interfaces. This allows you to pass value types without boxing.

interface IProcessor<T> { void Process(T item); } struct IntProcessor : IProcessor<int> { public void Process(int item) { /* ... */ } } static void RunProcessor<T>(IProcessor<T> processor, T item) => processor.Process(item); - Use Specific Overloads: Prefer method overloads that accept the specific value type rather than

object. Span<T>andMemory<T>(C# 7.2+): For high-performance memory manipulation, especially with contiguous memory blocks (like arrays or strings), these types allow you to work directly with the underlying data without allocations or boxing.params ReadOnlySpan<T>(C# 13+): This feature allows efficient handling ofparamsarrays of value types, avoiding the allocation of a temporary array and potential boxing.

3.6. Scope and Lifetime

While often used casually, “scope” and “lifetime” are distinct concepts in C# with specific implications for how variables and objects are managed.

Scope (Lexical Scope / Compile-Time)

Scope defines the region of code within which a particular variable, method, or type is visible and can be accessed. It is primarily a compile-time concept, determined by the lexical structure (curly braces {}) of your source code.

- Block Scope: Variables declared within a code block (e.g., inside an

ifstatement,forloop, or method body) are only accessible within that block. Once execution leaves the block, the variable goes out of scope.void MyMethod() { int x = 10; // x is scoped to MyMethod if (x > 5) { string message = "Hello"; // message is scoped only to this 'if' block Console.WriteLine(message); } // Console.WriteLine(message); // Compile-time Error: 'message' does not exist in the current context } // x goes out of scope here - Method Scope: Parameters and local variables are scoped to the method they are declared in.

- Class/Struct Scope: Fields and methods are scoped to the class or struct they belong to. Access modifiers (

public,private,internal,protected,file) further refine visibility. - Namespace Scope: Types are scoped to their containing namespace.

- File Scope (C# 10+, C# 11+): With file-scoped namespaces (C# 10) and the

fileaccess modifier for types (C# 11), visibility can be constrained to a single source file, useful for utility types that don’t need broader exposure.

Scope is solely about visibility and accessibility enforced by the C# compiler.

Lifetime (Runtime / Memory Management)

Lifetime, in contrast, refers to how long the memory occupied by a variable’s value or an object instance persists at runtime. This is managed by the CLR.

- Stack-Allocated Data (Value Types, References):

- Lifetime: The lifetime of variables stored on the stack (e.g., local value type instances, local reference variables) is deterministically tied to the execution of the method. When a method returns, its entire stack frame is “popped,” and all data within that frame is instantly deallocated.

- Example: In

int x = 10;,x’s lifetime ends precisely when the method it’s declared in finishes execution.

-

Heap-Allocated Objects (Reference Type Instances, Boxed Value Types):

- Lifetime: The lifetime of objects residing on the managed heap is governed by the Garbage Collector. An object on the heap remains “alive” as long as it is reachable by the application. An object is reachable if there is at least one “root” reference pointing to it (e.g., a static field, a local variable on the stack, a CPU register, or a reference from another live heap object).

- Non-Deterministic Deallocation: When an object becomes unreachable (meaning no active references point to it), it becomes eligible for garbage collection. The GC will eventually reclaim its memory, but when this happens is non-deterministic and depends on factors like available memory, GC heuristics, and the specific GC mode (workstation vs. server, concurrent vs. non-concurrent). You cannot explicitly

deletean object in C#. -

Example:

class LargeData { public byte[] data = new byte[1000000]; } void CreateAndForget() { LargeData d = new LargeData(); // 'd' (reference) on stack, LargeData object on heap. // When CreateAndForget() returns, 'd' goes out of scope and its stack lifetime ends. // The LargeData object on the heap is now unreferenced and becomes eligible for GC. } // The LargeData object's memory will be reclaimed *later* by the GC at an unspecified time.It’s important to note that a variable going out of scope does not immediately mean the object it referenced on the heap is deallocated. The object’s lifetime continues as long as any reachable reference to it exists. Conversely, an object might still be in scope (e.g., a static field that was set to

null), but if its reference is broken, the object it pointed to becomes eligible for GC.

Understanding this clear distinction between compile-time scope and runtime lifetime is vital for managing memory, avoiding memory leaks (by ensuring objects become unreachable), and correctly handling resources that are not managed by the GC (e.g., file handles, network connections, which require explicit disposal, as covered in Chapter 4).

3.7. Default Values and the default Keyword

In C#, variables are always initialized to a predictable state upon declaration. The compiler and runtime enforce rules regarding default values to prevent the use of uninitialized memory, which is a common source of bugs in languages like C++.

For more details on default values, see the official documentation.

Implicit Default Initialization

The behavior of default initialization depends on where a variable is declared:

- Fields of Classes and Structs: All fields (instance variables) of a class or a struct are automatically initialized to their default values by the CLR. This happens regardless of whether an explicit constructor is called. This ensures that an object or struct always starts in a known state.

- Array Elements: When an array is created using

new[], all its elements are automatically initialized to their respective type’s default value. - Local Variables (Crucial Difference): Unlike fields and array elements, local variables declared within methods are not automatically initialized by the runtime. The C# compiler strictly enforces the “definite assignment rule”: you must explicitly assign a value to a local variable before you can read from it. Attempting to use an unassigned local variable will result in a compile-time error. This design prevents common bugs where uninitialized values might lead to unpredictable behavior.

Default Values for Built-in Types

| Type Category | Type Example | Default Value |

|---|---|---|

| Integral Numeric Types | int, byte, long, short, sbyte, uint, ulong, ushort |

0 |

| Floating-Point Types | float, double |

0.0 |

| Decimal Type | decimal |

0.0M |

| Boolean Type | bool |

false |

| Character Type | char |

\0 (the null character, Unicode code point 0) |

| Enumeration Types | Any enum |

The value 0 (even if no enum member is explicitly assigned 0) |

| Reference Types | Any class (including string), interface, delegate, array |

null |

Value Types (struct) |

Any struct |

All its fields are recursively initialized to their own default values. |

Example of Default Initialization:

class Item

{

public int Quantity; // Defaults to 0

public bool IsAvailable; // Defaults to false

public string Description; // Defaults to null

public ProductInfo Details; // Details.Id will be 0, Details.Name will be null, Details.Price will be 0.0M

}

struct ProductInfo // Defined in section 3.3

{

public int Id;

public string Name;

public decimal Price;

}

void DemonstrateDefaults()

{

Item newItem = new Item(); // Fields of newItem are default-initialized

Console.WriteLine($"Quantity: {newItem.Quantity}"); // Output: Quantity: 0

Console.WriteLine($"IsAvailable: {newItem.IsAvailable}"); // Output: IsAvailable: False

Console.WriteLine($"Description: {newItem.Description ?? "null"}"); // Output: Description: null

Console.WriteLine($"Details.Id: {newItem.Details.Id}"); // Output: Details.Id: 0

int localCounter; // Local variable - not automatically initialized

// Console.WriteLine(localCounter); // Compile-time Error: Use of unassigned local variable 'localCounter'

localCounter = 10;

Console.WriteLine(localCounter); // Output: 10

}

The default Keyword (default(T) or just default)

The default keyword provides a convenient and type-safe way to explicitly obtain the default value for any given type. This is particularly useful in generic contexts where the specific type T is not known at compile time.

default(T): This is the traditional syntax, returning the default value for the specified type argumentT.defaultliteral: Introduced in C# 7.1, this simplified syntax allows you to omit the type argument when the compiler can infer the type from the context (e.g., assignment target, return type).

// Using default(T) explicitly

T GetDefaultValue<T>()

{

return default(T);

}

Console.WriteLine(GetDefaultValue<int>()); // Output: 0

Console.WriteLine(GetDefaultValue<string>() ?? "null"); // Output: null

Console.WriteLine(GetDefaultValue<DateTime>()); // Output: 1/1/0001 12:00:00 AM (default DateTime is its MinValue)

// Using the default literal (C# 7.1+)

int x = default; // x is 0 (type inferred from context)

string s = default; // s is null

bool b = default; // b is false

ProductInfo defaultProduct = default; // defaultProduct's fields are all default-initialized

// In contexts where the type is clear

Func<int> getDefaultInt = () => default; // Type is inferred as int

Console.WriteLine(getDefaultInt()); // Output: 0

The default keyword ensures that you can always obtain the appropriate initial value for any type, promoting code correctness and consistency, especially when writing generic algorithms.

Key Takeaways

- The Stack and the Heap: The Stack is a fast, LIFO region for method execution, local value types, and object references; its memory is deterministically deallocated. The Heap is a slower, dynamic region for all reference type instances, managed non-deterministically by the Garbage Collector.

- The Great Unification:

System.Object: All C# types ultimately derive fromSystem.Object. It provides core methods (e.g.Equals,GetHashCode,ToString,GetType) and establishes the concept of a Method Table (MT) as the static blueprint for every type definition, containing essential metadata for the CLR. - Value Types (

struct):- Directly contain their data, implicitly inherit from

System.ValueType. - Stored on the stack (for locals/params) or inline within reference types on the heap.

System.ValueTypeexists as a marker and provides default value-basedEqualsandGetHashCodeoverrides.- Unboxed instances do NOT contain an MT pointer: This is a memory optimization because structs lack inheritance and virtual methods, allowing compile-time/JIT-time method resolution.

- Exhibit copy semantics: assignments create full independent copies.

newoperator for structs initializes memory but does not cause heap allocation (unless array creation or boxing).- Generally performant due to stack allocation and less GC pressure, but copy costs for large structs can be a trade-off (mitigated by

inparameters).

- Directly contain their data, implicitly inherit from

- Reference Types (

class):- Store a reference to their data, which always resides on the heap. Inherit directly from

System.Object. - Every object on the heap has an Object Header (approx. 16-24 bytes) containing a Method Table Pointer and Sync Block Index.

- The Method Table for reference types is pointed to by every instance and contains detailed information: V-Tables for virtual dispatch, type identity, object layout, static field pointers, and flags. It is the basis for runtime type information and reflection (

System.Type,TypeHandle). - Exhibit reference semantics: assignments copy references, leading to shared state.

stringis a special immutable reference type with interning.- Incur heap allocation and contribute to GC pressure.

- Store a reference to their data, which always resides on the heap. Inherit directly from

- Boxing and Unboxing:

- Boxing converts a value type to an

object(or interface) by allocating a new heap object, copying the value type’s data into it, and returning a reference. The boxed object includes a full object header with an MT pointer. - Unboxing is the reverse.

- These are expensive operations due to heap allocations, data copying, and increased GC pressure, and should be avoided in hot code paths, typically by using generics.

- Boxing converts a value type to an

- Scope vs. Lifetime: Scope is a compile-time concept determining variable visibility. Lifetime is a runtime concept determining how long memory persists. Stack-allocated data has deterministic lifetime; heap-allocated objects have non-deterministic lifetime managed by the GC based on reachability.

- Default Values: Fields and array elements are automatically initialized to

0,false,null, etc. Local variables must be explicitly assigned before use. Thedefaultkeyword (default(T)ordefault) provides a type-safe way to obtain these default values, especially useful in generics.

4. Memory Management and Garbage Collection

In the realm of modern programming languages, automatic memory management has become a cornerstone, liberating developers from the error-prone complexities of manual memory allocation and deallocation. C# and .NET leverage a sophisticated Garbage Collector (GC) to handle memory, significantly enhancing developer productivity and reducing common bugs like memory leaks and dangling pointers. However, mastering C# at an expert level necessitates a deep understanding of how this automatic system works, its nuances, and how to interact with it effectively to build high-performance, robust applications.

This chapter will delve into the intricacies of the .NET Garbage Collector, exploring its generational approach, the specialized Large Object Heap, strategies for deterministic resource cleanup, advanced GC modes, and the role of weak references.

4.1. The .NET Generational Garbage Collector

The .NET GC is a tracing garbage collector, meaning it periodically identifies and reclaims memory occupied by objects that are no longer “reachable” by the application, but it doesn’t keep explicit reference counts (e.g. like Python). This process is automatic, but understanding its mechanics is crucial for diagnosing performance issues and writing GC-friendly code.

For a foundational understanding, consult the Fundamentals of Garbage Collection on Microsoft Learn.

Why a Garbage Collector?

Historically, languages such as C and C++ required developers to explicitly manage memory through functions like malloc/free or new/delete. This manual approach, while offering ultimate control, introduced a plethora of common and difficult-to-diagnose bugs:

- Memory Leaks: Forgetting to free allocated memory, leading to a gradual depletion of available RAM and potential application crashes or system instability.

- Dangling Pointers: Accessing memory after it has been freed, which can result in unpredictable behavior, data corruption, or security vulnerabilities.

- Double-Free Errors: Attempting to free the same block of memory twice, typically leading to crashes or heap corruption.

- Use-After-Free Vulnerabilities: A specific type of dangling pointer bug where an attacker can exploit freed memory.

The GC abstracts these complexities away, allowing developers to focus on application logic rather than memory management.

The Generational Hypothesis: The Strategy for Efficiency

The cornerstone of the .NET GC’s efficiency is the Generational Hypothesis. This empirically derived principle dictates that:

- Most objects are short-lived: A significant majority of newly created objects (e.g., local variables, temporary strings, loop iterators, intermediate results) become unreachable very quickly after their creation.

- The older an object is, the longer it is likely to live: Objects that survive initial collections tend to be part of the application’s long-term state and are likely to persist for a considerable duration.

This hypothesis directly informs the GC’s strategy: it’s more efficient to perform frequent, small collections on “young” objects (where most garbage resides) than to constantly scan the entire heap for dead objects.

The Managed Heap

The managed heap is the region of memory where reference type objects are allocated by the CLR. Crucially, the managed heap is not typically a single, giant, contiguous block of virtual memory. Instead, it is composed of one or more segments.

- What is a Segment? A segment is a contiguous chunk of virtual memory that the CLR requests from the operating system. These segments are usually of a fixed size, for example, 16MB for 64-bit Workstation GC, or larger for Server GC.

- Dynamic Growth: The CLR acquires new segments from the operating system as the managed heap needs to grow. This dynamic allocation allows the heap to expand only as much as necessary, rather than reserving a massive chunk of memory upfront.

- Organization: The segments collectively form the logical managed heap, and the garbage collector organizes and manages objects within and across these segments.

Generations 0, 1, and 2

The .NET GC divides the managed heap into three distinct generations to leverage the generational hypothesis:

-

Generation 0 (Gen 0):

- Purpose: This is where all newly allocated objects (reference types) are initially placed.

- Location: Gen 0 always resides at the ends of the segments.

- Size: Gen 0 is relatively small compared to other generations.

- Collection Frequency: Collected very frequently. When Gen 0 fills up, a Gen 0 collection is triggered. This is the fastest and most common type of GC, as it only needs to scan a small portion of the heap.

- Survival (Promotion): Objects that are still reachable after a Gen 0 collection are “promoted” to Generation 1. This involves moving their data to the Gen 1 area.

-

Generation 1 (Gen 1):

- Purpose: Holds objects that survived one Gen 0 collection. These are slightly longer-lived than typical Gen 0 objects but are still considered relatively young.

- Location: Gen 1 typically shares space within the ephemeral segment with Gen 0, or occupies the next older segment.

- Size: Larger than Gen 0, but smaller than Gen 2.

- Collection Frequency: Collected less frequently than Gen 0. A Gen 1 collection occurs when Gen 1 fills up, or if a Gen 0 collection fails to free enough memory.

- Survival (Promotion): Objects that survive a Gen 1 collection are promoted to Generation 2.

-

Generation 2 (Gen 2):

- Purpose: Contains long-lived objects that have survived multiple collections (from Gen 1), as well as all objects allocated on the Large Object Heap (LOH).

- Location: Gen 2 typically occupies the oldest segments of the heap. As Gen 2 grows due to promotions, the CLR may acquire new segments specifically for Gen 2, adding them to the collection of segments managed by the GC.

- Size: Largest generation.

- Collection Frequency: Collected least frequently. A Gen 2 collection (often referred to as a “full GC”) is the most expensive, as it involves scanning the entire managed heap across all segments. It occurs when Gen 2 fills up, or when available memory is critically low, or occasionally by GC heuristics.

- Survival: Objects in Gen 2 generally remain there for a significant portion of the application’s lifetime, being collected only when they become truly unreachable.

This generational design significantly improves GC performance. By concentrating collection efforts on the youngest generation (where most dead objects are), the GC avoids the overhead of constantly scanning the entire, potentially massive, heap.

Object Allocation

When you create a new instance of a reference type using the new operator (e.g., new MyClass()), the allocation process is incredibly fast. The CLR manages a simple allocation pointer, which tracks the “end” of the current Gen 0 segment.

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Managed Heap (Conceptual View) |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Segment 1 (Acquired First) Segment 2 (Acquired Later) ... |

| +-------------------------+ +--------------------------+ |

| | Gen 2 Objects | | Gen 2 Objects | |

| | Gen 1 Objects | | Gen 1 Objects | |

| | Gen 0 Objects | | Gen 0 Objects (New Alloc)| <-- Allocation Pointer

| +-------------------------+ +--------------------------+ |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

- Speed: New objects are almost always allocated into Generation 0 (the youngest generation) by simply moving this pointer forward. This is akin to allocating memory on the stack: it’s a simple pointer increment, as Generation 0 is designed to be a completely contiguous block of free space at the “end” of the current managed segment.

- Contiguous Free Space: This efficient allocation relies on the fact that the garbage collector keeps Generation 0 free of fragmentation, ensuring there’s always a clean, contiguous block of memory ready for new objects.

- Segment Boundary: When the current segment is full (or the available space for Gen 0 is exhausted), a garbage collection is triggered, or a new segment might be acquired from the OS to continue allocations.

The Mark-and-Compact Algorithm

The core algorithm used by the .NET GC to reclaim memory and manage fragmentation is a variant of the mark-and-compact algorithm (though modern GCs often employ sophisticated concurrent and background phases, the principles remain).

-

Mark Phase:

- The GC identifies all “roots” of the object graph. Roots are starting points from which objects can be reached, effectively defining what is “live.” These include:

- Static fields (references held by static variables).

- Stack variables (references held by local variables and method parameters on thread stacks).

- CPU registers (references held by CPU registers).

- GC Handles (explicitly created references for interop, pinning, etc.).

- The Finalization Queue (references to objects awaiting finalization).

- Starting from these roots, the GC recursively traverses the graph of objects, marking every object it encounters as “reachable” (or “live”).

- Any object not marked as reachable after this phase is considered “unreachable” (or “dead”) and is eligible for collection.

- The GC identifies all “roots” of the object graph. Roots are starting points from which objects can be reached, effectively defining what is “live.” These include:

-

Relocate/Compact Phase:

- After identifying live objects within a segment, the GC then moves these live objects to contiguous blocks within that segment (or sometimes to a younger segment during promotion).

- Eliminates Fragmentation: By relocating live objects side-by-side, compaction effectively removes the “holes” (free memory regions) left by dead objects, consolidating all available free space into one large, contiguous block at the end of the segment.

- Faster Future Allocations: This contiguous free space is essential for the highly efficient, pointer-increment-based allocation for new Gen 0 objects.

- Updates References: As objects are moved, the GC automatically updates all references (pointers) to these moved objects throughout the entire object graph (on the stack, in CPU registers, and within other heap objects) to point to their new locations.

- Segment Management and Compaction: While compaction primarily occurs within individual segments to maintain their contiguity, a full Gen 2 GC can involve more complex movements between segments, especially when promoting objects or when aiming to reclaim entire unused segments. The goal is always to consolidate free space and maintain allocation speed.

-

Sweep Phase (Conceptual):

- The memory regions previously occupied by dead objects, now empty due to compaction, are implicitly made available for new allocations. This is often integrated into the compaction process.

Segment Before GC (Fragmented)

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+ (A,B,C,D,E = Live; X,Y,Z,W = Dead)

| A | X | B | Y | C | Z | D | W | E |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^ Mark Phase: Identify A,B,C,D,E as live

Segment After GC (Compacted)

+---+---+---+---+---+---------------+

| A | B | C | D | E | | (Live objects moved to front within the segment)

+---+---+---+---+---+---------------+

^ Contiguous Free space for new allocations (Gen 0)

GC Triggers

Garbage collections are triggered by various factors, primarily:

- Generation 0 Full: The most common trigger. When the allocation pointer in Gen 0 reaches the end of its available space within the current segment, a Gen 0 collection is initiated.

- Memory Pressure: If the system reports low available memory, the GC might trigger a collection (potentially a full Gen 2 collection) to free up resources.

- Explicit Calls (

GC.Collect()): While possible, explicitly callingGC.Collect()is almost universally discouraged in production code. The GC’s sophisticated heuristics are usually far better at determining the optimal time for collection than manual intervention. Manual calls can disrupt these heuristics, leading to less efficient overall memory management and potentially introducing performance bottlenecks due to unexpected pauses.

4.2. The Large Object Heap (LOH)

While the generational GC effectively compacts memory for small and medium-sized objects, moving very large objects during compaction would be prohibitively expensive due to the sheer volume of data being copied. To address this, the .NET CLR introduced the Large Object Heap (LOH).

Refer to the Large Object Heap (LOH) documentation on Microsoft Learn.

Understanding LOH Allocation

- Threshold: Objects greater than or equal to 85,000 bytes (83 KB) are allocated on the LOH. Common examples include large arrays (e.g.,

int[],double[]) and large strings (though strings are immutable, forming a new large string often involves LOH). - No Compaction (Historically): Traditionally, the LOH was not compacted. Once a large object was allocated, it stayed at its memory address within its segment. When a large object died, its memory was simply marked as free, creating a “hole” in that LOH segment.

-

Fragmentation Problem: Because the LOH typically doesn’t compact (or historically, didn’t at all), it’s highly susceptible to fragmentation. As large objects of varying sizes die, they leave gaps of different sizes within the LOH segments. If a new large object needs to be allocated, it might not find a contiguous free block large enough, even if the total free memory on the LOH is sufficient across all segments. This can lead to

OutOfMemoryExceptioneven when physical memory is plentiful.LOH (Fragmented) - within a single LOH segment +-----------+---------+-----------+-----------+---------+ | Object A | Free | Object B | Free | Object C| | (100KB) | (50KB) | (120KB) | (80KB) | (90KB) | +-----------+---------+-----------+-----------+---------+ // there is a total of 50KB + 80KB = 130KB free space, // but if a new 100KB object needs to be allocated, it won't fit - LOH Collection: LOH collections occur only during Generation 2 collections. This means that dead large objects might persist in memory for a longer time before being reclaimed, exacerbating fragmentation within their LOH segments.

Modern LOH Improvements (.NET 7+)

With .NET 7 and later, significant improvements have been made to the LOH and compaction, mitigating some of the historical fragmentation issues:

- LOH Compaction: The LOH is now eligible for compaction during a full (Gen 2) GC, though it’s not compacted by default every time. This means that, when certain conditions are met, the GC can compact live objects within LOH segments to reduce fragmentation. You can influence this behavior via

GCSettings.LargeObjectHeapCompactionMode. - Pinned Object Heap (POH): Objects that must be fixed in memory (e.g., for native interop or

fixedstatements) are allocated on the POH, a separate heap that is never compacted. This prevents pinning from interfering with the compaction of other objects on the regular heap, as well as the LOH. - Non-LOH objects eligible for compaction: Even objects smaller than the LOH threshold can sometimes be allocated in segments that don’t get compacted, for example, if they are pinned. Modern GC aims to reduce pinning overhead on compaction where possible.

These improvements mitigate some of the historical pain points of LOH fragmentation.

Mitigating LOH Impact

Despite improvements, being mindful of LOH allocations remains important for performance:

-

Object Pooling (e.g.,

ArrayPool<T>): Instead of allocating new large arrays repeatedly, useArrayPool<T>.Sharedto rent and return arrays. This significantly reduces LOH allocation and GC pressure.using System.Buffers; byte[] buffer = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(100_000); // Rents a buffer from the pool try { // Use the buffer } finally { ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Return(buffer); // Return to the pool for reuse } Span<T>andMemory<T>: These types (introduced in C# 7.2) allow you to work with segments of memory (including large arrays) without creating new copies or allocations, thereby reducing the need for new large objects and minimizing LOH pressure.- Immutable Strings: Remember that

stringoperations often create new strings. For extensive string manipulation, useStringBuilderto reduce intermediate string allocations.

4.3. Finalization and IDisposable

The Garbage Collector effectively manages managed memory (memory allocated by the CLR for C# objects). However, applications often interact with unmanaged resources, which the GC cannot directly manage. Examples include:

- File handles (

FileStream) - Network sockets (

Socket) - Database connections (

SqlConnection) - Graphics handles (GDI+, DirectX)

- Native memory buffers (allocated via

Marshal.AllocHGlobal)

Failure to release these unmanaged resources deterministically can lead to resource leaks (e.g., too many open files, exhausted socket pool) even if managed memory is being cleaned up correctly. C# provides two mechanisms for resource cleanup: Finalizers (non-deterministic) and IDisposable (deterministic).

Non-Deterministic Finalization (Finalizers)

A finalizer (historically called a destructor in C++, often misrepresented as such in C# context) is a special method defined using a tilde (~) before the class name (e.g., ~MyClass()).

-

How it Works:

- When an object with a finalizer is created, the CLR adds a reference to it to a special internal list called the finalization queue.

- When the GC determines that an object with a finalizer is no longer reachable, it does not immediately reclaim its memory. Instead, it moves the object to another internal queue called

freachable(finalization-reachable queue). - A dedicated finalizer thread (run by the CLR) periodically processes the

freachablequeue, executing each object’s finalizer method. - Only after the finalizer has successfully run can the object’s memory be reclaimed by a subsequent GC collection cycle.

-

Drawbacks and Why They Are Discouraged:

- Non-Deterministic: You have no control over when a finalizer will run. It could be seconds, minutes, or never (if the application terminates abruptly before GC runs). This means unmanaged resources could be held for an unacceptably long time.

- Performance Overhead: Objects with finalizers are more expensive for the GC to manage. They effectively survive at least one extra GC collection to allow their finalizer to run, and the finalizer thread’s work can introduce overhead.

- Order Not Guaranteed: The order in which finalizers run is not guaranteed, even for related objects. This makes it dangerous to rely on finalizers to clean up dependent resources.

- Can Block GC: A slow or buggy finalizer can block the finalizer thread, potentially stalling the GC process and leading to memory pressure.

- Anti-pattern for Most Cases: Due to these issues, finalizers are almost universally discouraged as a primary cleanup mechanism for application code. They are generally only used in base classes by framework developers as a last-resort safeguard against resource leaks if

IDisposableis not used correctly.

// Example (Don't do this for primary cleanup!)

class MyResourceHolder

{

private IntPtr _unmanagedBuffer; // Example of unmanaged resource

public MyResourceHolder()

{

_unmanagedBuffer = System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.AllocHGlobal(1024);

Console.WriteLine("MyResourceHolder created, unmanaged buffer allocated.");

}

// Finalizer (called non-deterministically by GC)

~MyResourceHolder()

{

Console.WriteLine("Finalizer running for MyResourceHolder.");

System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.FreeHGlobal(_unmanagedBuffer);

Console.WriteLine("Unmanaged buffer freed by finalizer.");

}

}

Deterministic Cleanup (IDisposable)

The System.IDisposable interface provides the standard, deterministic way to release unmanaged resources and clean up other managed resources.

IDisposableInterface: It defines a single method:void Dispose().public interface IDisposable { void Dispose(); }- The

Dispose()Method: This method should contain all the logic necessary to release unmanaged resources (e.g., close files, free native memory) and optionally release large managed resources. - Manual Invocation: The key is that

Dispose()is meant to be called explicitly by the developer when they are finished with the resource. This provides deterministic cleanup – you know exactly when the resource is released. - The Dispose Pattern: For classes that own both managed and unmanaged resources, the standard “Dispose pattern” is recommended to prevent resource leaks and avoid double-disposal. This involves:

- Implementing

IDisposable. - Providing a

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)method. - The

Dispose()method callsDispose(true)andGC.SuppressFinalize(this). - If a finalizer is present, it calls

Dispose(false).

- Implementing

public class ManagedAndUnmanagedResource : IDisposable

{

private bool _disposed = false;

private System.IO.FileStream _fileStream; // Managed resource

private IntPtr _nativeBuffer; // Unmanaged resource

public ManagedAndUnmanagedResource(string filePath)

{

_fileStream = new System.IO.FileStream(filePath, System.IO.FileMode.Create);

_nativeBuffer = System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.AllocHGlobal(1024);

Console.WriteLine("Resource created: File and Native Buffer allocated.");

}

// Public method for explicit deterministic cleanup

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true); // Call the protected method, indicating explicit disposal

GC.SuppressFinalize(this); // Tell the GC not to call the finalizer

Console.WriteLine("Dispose() called explicitly. Suppressing finalizer.");

}

// Finalizer (present only if there's an unmanaged resource and Dispose might not be called)

~ManagedAndUnmanagedResource()

{

Console.WriteLine("Finalizer running (Dispose() was not called).");

Dispose(false); // Call the protected method, indicating disposal via finalizer

}

// The core cleanup logic

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (_disposed) {

return; // Already disposed

}

_disposed = true;

if (disposing)

{

// Clean up managed resources here

_fileStream?.Dispose(); // Dispose managed object

Console.WriteLine("Managed resource (FileStream) disposed.");

}

// Clean up unmanaged resources here (regardless of 'disposing' value)

if (_nativeBuffer != IntPtr.Zero)

{

System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.FreeHGlobal(_nativeBuffer);

_nativeBuffer = IntPtr.Zero;

Console.WriteLine("Unmanaged resource (Native Buffer) freed.");

}

}

}

using Statements and using Declarations

To simplify the deterministic disposal pattern, C# provides the using statement and using declarations (C# 8+). These constructs guarantee that Dispose() is called on an IDisposable object when the using block is exited, even if an exception occurs.

-

usingStatement (Traditional):// C# 7 and earlier using (var resource = new ManagedAndUnmanagedResource("log.txt")) { // Use the resource Console.WriteLine("Using the resource..."); } // resource.Dispose() is called automatically here Console.WriteLine("Resource disposed via using statement.");This is compiled into a

try-finallyblock that ensuresDispose()is called. -

usingDeclaration (C# 8.0+): This provides a more concise syntax forusingstatements, particularly useful when chaining multiple disposables or when the resource is used throughout a method. The resource is disposed at the end of the scope in which it is declared.// C# 8 and later void ProcessFile(string path) { using ManagedAndUnmanagedResource resource1 = new ManagedAndUnmanagedResource(path); using System.IO.StreamReader reader = new System.IO.StreamReader(resource1._fileStream); // Accessing for demo // Use resource1 and reader Console.WriteLine("Using declarations in scope..."); } // Both resource1.Dispose() and reader.Dispose() are called automatically here Console.WriteLine("Resources disposed via using declarations.");

IAsyncDisposable and await using (C# 8.0+)

For scenarios where resource disposal involves asynchronous operations (e.g., closing a network connection that requires asynchronous flushing), C# 8.0 introduced System.IAsyncDisposable and the await using construct.

IAsyncDisposableInterface: Defines a single asynchronous method:ValueTask DisposeAsync().public interface IAsyncDisposable { ValueTask DisposeAsync(); }-

await using: Similar tousing, but it awaits theDisposeAsync()method.public class AsyncResource : IAsyncDisposable { public async ValueTask DisposeAsync() { Console.WriteLine("Simulating async cleanup..."); await Task.Delay(100); // Simulate async work Console.WriteLine("Async cleanup complete."); } } async Task UseAsyncResource() { await using var resource = new AsyncResource(); Console.WriteLine("Using async resource..."); } // resource.DisposeAsync() is awaited hereThis is essential for robust asynchronous resource management without blocking threads.

Debate Simulation: Finalizers vs. IDisposable

- Argument for Finalizers: “They’re automatic! I don’t have to remember to call

Dispose().” - Counter-argument for Finalizers: “Yes, but they’re non-deterministic. Your critical database connection might stay open for minutes, or your limited native memory might not be freed until the GC feels like it. This leads to resource exhaustion and unreliable behavior. They also add GC overhead.”

- Argument for

IDisposable: “I have explicit control. I know exactly when my resources are released. Theusingstatement makes it easy and safe.” - Counter-argument for

IDisposable: “It requires manual intervention. What if I forget to put an object in ausingblock or callDispose()? Resource leaks!” - Conclusion: For application developers,