Part III: Core C# Types: Design and Deep Understanding

Part III of the C# Mastery Guide focuses on the core types and language features that form the backbone of C# programming. This section provides a deep understanding of classes, structs, interfaces, and other fundamental constructs, exploring their design, memory management, and advanced features introduced in recent C# versions.

Table of Contents

7. Classes: Reference Types and Object-Oriented Design Deep Dive

- 7.1. The Anatomy of a Class: Object Headers, understanding instance vs. static members, static constructors, and the

beforefieldinitflag. - 7.2. Constructors Deep Dive: Instance and static constructors, Object Initializers, Primary Constructors (C# 12), and derived class constructor resolution.

- 7.3. The

thisKeyword: Instance Reference and Context: Comprehensive coverage ofthisfor referring to the current instance and its contextual uses. - 7.4. Core Class Members: Properties, Indexers, and Events: Compiler transformations,

init-only setters,requiredmembers (C# 11),fieldkeyword (C# 11), and event mechanics. - 7.5. Class Inheritance: Foundations and Basic Design: How the CLR implements inheritance, the

basekeyword, and object slicing considerations. - 7.6. Polymorphism Deep Dive:

virtual,abstract,override, andnew: The concept of runtime polymorphism, method overriding, abstract members, and method hiding. - 7.7. Virtual Dispatch and V-Tables: A deep dive into virtual method tables (V-tables) and how the CLR uses them for dynamic dispatch.

- 7.8. The

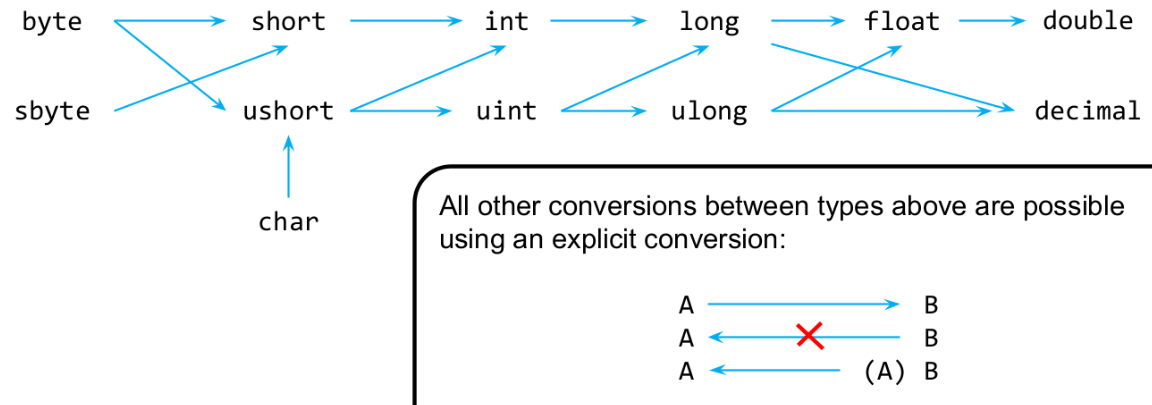

sealedKeyword: Usingsealedon types and methods to control inheritance and overriding, and its impact on performance. - 7.9. Type Conversions: Implicit, Explicit, Casting, and Safe Type Checks: Built-in conversions, explicit casting, and the

isandaskeywords for safe type checking. - 7.10. Operator Overloading and User-Defined Conversion Operators: How

op_methods enable custom operator behavior and type conversions. - 7.11. Parameter Modifiers:

ref,out,in, andrefVariables: Detailsref,out,inparameter modifiers for passing arguments by reference, along withreflocals and return types for direct memory aliases, emphasizing their distinct effects on value and reference types. - 7.12. Method Resolution Deep Dive: Overloading and Overload Resolution: Method overloading and the compiler’s algorithm for selecting the best method in complex scenarios, including inheritance.

- 7.13. Nested Types and Local Functions: Their IL representation, scope rules, and implications for closures.

8. Structs: Value Types and Performance Deep Dive

- 8.1. The Anatomy, Memory Layout, and Boxing of a Struct: Detailed memory layout on stack vs. heap, and the performance implications of boxing.

- 8.2. Struct Constructors and Initialization: Understanding default and Primary Constructors (C# 12),

readonlystructs, and field initialization. - 8.3. Struct Identity: Implementing

Equals()andGetHashCode(): Best practices for implementingEquals()andGetHashCode()for structs to ensure correctness and performance. - 8.4. Passing Structs:

in,ref,outParameters Revisited: Detailed IL and performance implications of passing structs byin,ref, andout. - 8.5. High-Performance Types:

ref struct,readonly ref struct, andref fields(C# 11): Deep dive into stack-only types likeref structand their role in high-performance APIs likeSpan<T>. - 8.6. Structs vs. Classes: Choosing the Right Type: A comprehensive comparison of structs vs. classes, guiding optimal type choice and performance trade-offs.

9. Interfaces: Contracts, Implementation, and Modern Features

- 9.1. The Anatomy of an Interface: Understanding interfaces as contracts without state, and their representation in IL.

- 9.2. Interface Dispatch: How interface method calls work via Interface Method Tables (IMTs), a mechanism distinct from class v-tables.

- 9.3. Interface Type Variables and Casting: Understanding interface type variables, their casting rules, and how they differ from class inheritance

- 9.4. Explicit vs. Implicit Implementation: How explicit implementation hides members and resolves naming conflicts when implementing multiple interfaces.

- 9.5. Interface and Inheritance: How interfaces can be used in inheritance hierarchies, including re-implementing inherited interfaces.

- 9.6. Modern Interface Features:

- Default Interface Methods (DIM) (C# 8): Adding default implementations to interfaces without breaking existing implementers.

- Static Abstract & Virtual Members in Interfaces (C# 11): The foundational feature enabling Generic Math, allowing polymorphism on static methods for a wide range of types.

10. Essential C# Interfaces: Design and Usage Patterns

- 10.1. Core Value Type Interfaces:

IComparable<T>,IComparer<T>,IEquatable<T>,IFormattable,IParsable<T>,ISpanFormattable,ISpanParsable<T>– their design, implementation, and compiler integration for type comparison, formatting, and parsing. - 10.2.

IEnumerable: The Magic Behindforeachand Iterator Methods: Understanding howIEnumerable<T>andIEnumerator<T>enable iteration over collections, the mechanics ofyield return, and the compiler-generated state machines that allow deferred execution. - 10.3. Collection Interfaces:

ICollection<T>,IList<T>,ISet<T>,IDictionary<TKey, TValue>and their read-only counterparts – understanding their contracts, common implementations, and performance characteristics. - 10.4. Resource Management:

IDisposable:IDisposableand theDisposemethod for deterministic resource cleanup, and its role in theusingpattern. - 10.5. Mathematical and Numeric Interfaces (Generic Math): A detailed look at interfaces like

IAdditionOperators<TSelf, TOther, TResult>,INumber<TSelf>, and others introduced in C# 11, and how they enable generic algorithms over numeric types.

Here is the summarized version of Chapter 10, formatted as requested for the Table of Contents:

11. Fundamental C# Types: Core Data Structures and Utilities

- 11.1. Strings: Immutability,

StringBuilder, and Performance: A comprehensive exploration ofstring’s immutable nature, string interning, performance considerations, andStringBuilderfor efficient mutable string operations. - 11.2. Enumerations (

enum): Underlying Types, Flags, and Best Practices: Understandingenuminternals, underlying integral types, the[Flags]attribute, and best practices for defining and consuming enumerations. - 11.3. Arrays and

List<T>: Memory, Performance, and Related Types: A deep dive intoSystem.ArrayandList<T>internals, including memory layout, dynamic resizing, and efficient interaction withSpan<T>andReadOnlySpan<T>. - 11.4. Hash-Based Collections:

Dictionary<TKey, TValue>andHashSet<T>: Examining the internal mechanisms of hash tables, including hashing algorithms, collision resolution, and the performance characteristics of these widely used collections. - 11.5. Tuples and

ValueTuple: Structure, Memory, and Modern Usage: Differentiating betweenTupleandValueTuple, exploring their memory layout, performance, and modern use for lightweight data aggregation. - 11.6. I/O Streams and Readers/Writers: Covering the

Streamhierarchy, and the internal workings, buffering, and resource management ofStreamReader/WriterandStringReader/Writerfor character-based I/O. - 11.7. Date, Time, and Unique Identifiers: A detailed look at the internal representations and best practices for handling temporal data with

DateTime,DateTimeOffset,DateOnly,TimeOnly, and unique identifiers withGuid. - 11.8.

Lazy<T>: Deferred Initialization and Resource Management: Understanding howLazy<T>enables efficient, on-demand object creation, its thread-safety mechanisms, and its use in optimizing resource allocation. - 11.9.

Random: Pseudorandomness, Seeding, and Thread Safety: Exploring the internal algorithms behind pseudorandom number generation, the importance of proper seeding, and considerations for thread safety when usingRandominstances. - 11.10.

Regex: Regular Expression Compilation and Performance: A deep dive into theRegexclass, covering its internal state machine, the performance implications of compiled vs. interpreted regular expressions, and strategies for optimizing regex usage.

11. Delegates, Lambdas, and Eventing: Functional Programming Foundations

- 11.1. Delegates Under the Hood: First-class functions in C#, the

MulticastDelegateclass, and the internals ofAction,FuncandPredicategeneric delegates. - 11.2. The

eventKeyword: Compiler generation ofadd_andremove_methods, ensuring thread safety for event subscriptions, and best practices for event design usingEventHandler<T>andEventHandlerdelegates. - 11.3. Lambdas and Closures: How the compiler transforms lambda expressions into hidden classes, and the precise mechanics of variable capture (closures) and their performance implications.

- 11.4. Expression Trees: Representing C# code as data structures (

System.Linq.Expressions.Expression) for runtime interpretation and modification, primarily used by LINQ providers (e.g., LINQ to SQL).

12. Modern Type Design: Records, Immutability, and Data Structures

- 12.1. Record Classes (

record classC# 9): Internals of compiler-generated methods for immutability, value-based equality,withexpressions, andToStringoverrides. - 12.2. Record Structs (

record structC# 10): Applying value-based equality, immutability, andwithexpressions to value types, and their memory layout considerations. - 12.3.

readonlyModifier Beyond Fields: Deep dive intoreadonly structandreadonly members(C# 8), ensuring immutability at the type and member level. - 12.4. Immutability Patterns: Strategies for designing and enforcing immutable types in C#, including the Builder pattern for complex object creation.

- 12.5. Frozen Collections (

System.Collections.Immutable): The immutable collection types provided bySystem.Collections.Immutableand their benefits for concurrent and predictable data structures.

13. Nullability, Safety, and Defensive Programming

- 13.1. The

nullKeyword: Hownullreferences are represented in the CLR and the ubiquitousNullReferenceException. - 13.2. Nullable Reference Types (NRTs) (C# 8+): The compiler’s flow analysis for nullability, nullable annotations (

?), the null-forgiving operator (!), and#nullable enable/disabledirectives. The philosophical shift towards compile-time null safety. - 13.3. Nullable Value Types (

Nullable<T>): The struct’s internals,HasValue,Value, and implicit conversions to and from the underlying type. - 13.4. Null Coalescing and Conditional Operators: The

??,??=,?., and!. operators, their IL representation, and how they improve code safety and readability by handling nulls concisely. - 13.5.

requiredMembers (C# 11): Ensuring proper initialization of members at compile-time for objects, enforcing design contracts. - 13.6. The

nameofOperator: Usingnameofto obtain the string name of a variable, type, or member at compile time, improving refactoring safety and debugging/logging. - 13.7.

throwexpressions (C# 7): Usingthrowas an expression to make error handling more concise in ternary operations, lambda bodies, or property accessors.

7. Classes: Reference Types and Object-Oriented Design Deep Dive

In C#, classes serve as the blueprints for objects, embodying the principles of object-oriented programming. As reference types, instances of classes are allocated on the managed heap, their lifetimes governed by the garbage collector. This chapter moves beyond basic class usage to dissect their internal structure, initialization semantics, member behaviors, and the foundational concepts of inheritance and polymorphism, ultimately aiming to foster an expert-level understanding of how C# classes truly operate from source code to native execution.

7.1. The Anatomy of a Class

To truly understand how classes work, we must first look under the hood at how an object instance is represented in memory and how its members are structured. This low-level view provides crucial insights into performance and runtime behavior.

Object Headers and the MethodTable Pointer

When you instantiate a class using new, the Common Language Runtime (CLR) allocates a block of memory on the managed heap. This memory isn’t just for your instance’s fields; it includes crucial metadata managed by the CLR.

Every object on the managed heap starts with an Object Header. In modern .NET (e.g., .NET 6+), this header typically occupies 8 bytes on a 64-bit system (or 4 bytes on a 32-bit system) and contains two primary components:

- Sync Block Index (or Monitor Table Index): This portion is used for thread synchronization (e.g.,

lockstatements) and storing various flags for the garbage collector (GC), such as object age, whether it’s pinned, etc. It’s often lazily initialized. - MethodTable Pointer (MT Ptr): This is arguably the most important part for understanding object behavior. It’s a pointer to the type’s MethodTable (also known as Type Handle or Class Object), which resides in a special area of memory called the AppDomain’s loader heap. The MethodTable is essentially the CLR’s internal representation of the class itself, containing:

- Information about the type’s base class.

- Interface implementations.

- Metadata about the type’s fields (names, types, offsets).

- Pointers to JIT-compiled native code for all type methods, including instance methods, static methods, and constructors.

- Pointers to the methods implemented by the type. For virtual methods, this will typically include a pointer to the Virtual Method Table (V-Table), which we’ll explore in detail in section 7.7.

This view of the Method Table is heavily simplified and it is explained in more detail in Chapter 3

Conceptual Diagram of an Object in Memory:

[Managed Heap]

+-------------------+

| [Object Header] | <-- object reference (lives on stack) (8 bytes on 64-bit)

| - Sync Block |

| - MethodTable Ptr | ----> [AppDomain's Loader Heap]

+-------------------+ +-----------------------+

| Instance Field 1 | | MethodTable |

| Instance Feild 2 | +-----------------------+

| ... | | Base Type MT Pointer |

+-------------------+ | Interface Map |

| Field Layout Info |

| Ptr to Method 1 Code |

| Ptr to Method 2 Code |

| ... |

| (Ptr to V-Table) |

+-----------------------+

When you call a method on an object, the CLR uses the MethodTable pointer to find the correct method implementation for that object’s specific type. This is crucial for runtime polymorphism.

Understanding Instance vs. Static Members

C# differentiates between members that belong to a specific instance of a class and those that belong to the type itself.

-

Instance Members:

- Fields: These hold data unique to each object instance. They are allocated within the memory block of the object itself on the managed heap.

- Methods: These operate on the data of a specific object instance. They are invoked via an object reference, and implicitly receive the

thispointer (explained in 7.3) to access the instance’s fields and other methods. - Properties, Indexers, Events: These are syntactic sugar for instance methods (as detailed in 7.4) and thus also belong to instances.

public class Car { // Instance field public string Model { get; set; } // Instance method public void Drive() { Console.WriteLine($"Driving {Model}"); } } // Usage: Car myCar = new Car { Model = "Sedan" }; // 'Model' belongs to 'myCar' myCar.Drive(); // 'Drive' operates on 'myCar' -

Static Members:

- Fields: These hold data that is shared by all instances of the class, or data that pertains to the type as a whole. Static fields are allocated in a special memory region within the AppDomain’s loader heap (part of the MethodTable’s associated data), not within individual object instances.

- Methods: These operations do not operate on a specific instance’s data. They are invoked directly on the type name and do not have access to the

thispointer. They are typically used for utility functions, factory methods, or operations that affect the class as a whole. - Properties, Events: Can also be static, behaving similarly to static methods/fields.

public class Car { // Static field: shared by all Car objects public static int NumberOfCarsCreated { get; private set; } = 0; // Static method: operates on type-level data public static void DisplayTotalCars() { Console.WriteLine($"Total cars created: {NumberOfCarsCreated}"); } public Car() // Instance constructor { NumberOfCarsCreated++; // Increments the static field } } // Usage: Car car1 = new Car(); Car car2 = new Car(); Car.DisplayTotalCars(); // Output: Total cars created: 2

Static Constructors and their Execution Order

A static constructor is a special parameterless constructor that belongs to the type itself, not to any specific instance. Its primary purpose is to initialize static fields or to perform any one-time setup for the type.

For more details on static constructors, see the C# Language Specification.

Key characteristics and guarantees:

- Parameterless and Public/Private: Static constructors cannot have parameters and are implicitly

private. You cannot specifypublic,protected,internal, orprivateexplicitly. - No Explicit Invocation: You cannot call a static constructor directly from your code. The CLR automatically invokes it.

- Guaranteed Single Execution: The CLR guarantees that a static constructor will execute at most once for a given AppDomain.

-

Guaranteed Execution Timing: The static constructor is guaranteed to run before any of the following events occur for that type:

- The first instance of the type is created.

- Any static member of the type (including static methods, properties, or fields, but excluding literal constants) is accessed.

This guarantee ensures that static fields are in a valid state and any type-specific setup is completed before the type is used.

class BaseClass { static BaseClass() => Console.WriteLine("BaseClass static constructor"); public BaseClass() => Console.WriteLine("BaseClass instance constructor"); } class DerivedClass : BaseClass { static DerivedClass() => Console.WriteLine("DerivedClass static constructor"); public DerivedClass() => Console.WriteLine("DerivedClass instance constructor"); } // Creating an instance of DerivedClass Console.WriteLine("Creating a new DerivedClass instance..."); DerivedClass obj = new DerivedClass(); Console.WriteLine("Instance created!"); // Output: // Creating a new DerivedClass instance... // DerivedClass static constructor // BaseClass static constructor // BaseClass instance constructor // DerivedClass instance constructor // Instance created!Notice that all static constructors in the inheritance chain are executed before any instance constructor. This ensures that the base class is fully initialized before the derived class’s static constructor runs.

The beforefieldinit Flag

The CLR’s guarantee for static constructors (execution before any static member access or instance creation) comes with a performance cost: it requires runtime checks. To optimize this, the C# compiler (and other .NET language compilers) often emit a special flag called beforefieldinit into the type’s metadata.

- What

beforefieldinitdoes: When a type has thebeforefieldinitflag (which is the default behavior for types without an explicitly declared static constructor), the CLR is allowed to initialize static fields at any point before their first static field access. This often means the static fields are initialized when the type is first loaded by the CLR, which can be much earlier than when they are actually used. This avoids the runtime checks associated with guaranteeing static constructor execution time. - When it’s present: The C# compiler adds the

beforefieldinitflag to a type if it does not have a static constructor but does have static field initializers. - When it’s absent: If you explicitly declare an empty static constructor (

static MyClass() { }), or any static constructor at all, the C# compiler will not emit thebeforefieldinitflag. In this case, the CLR will strictly adhere to the static constructor guarantees (execution before first static member access or instance creation).

Understanding beforefieldinit is crucial for debugging subtle timing issues related to static field initialization and for understanding the CLR’s optimization strategies. For most applications, the default beforefieldinit behavior is harmless and beneficial for performance, but it’s important to be aware of when it’s not applied due to an explicit static constructor.

Declaring and Instantiating New Type Instances

C# offers several syntactic options for declaring and instantiating new objects. The choice of syntax can affect code readability, type inference, and sometimes brevity. Here are the most common patterns:

1. Explicit Type Declaration with Constructor

Car c = new Car();

- Explanation: The variable

cis explicitly declared as typeCar, and a new instance is created using theCarconstructor. - When to use: When you want to be explicit about the variable’s type, which can improve code clarity, especially for readers unfamiliar with the type.

2. Explicit Type Declaration with Target-Typed new (C# 9+)

Car c = new();

- Explanation: The variable

cis declared as typeCar, and thenew()expression infers the type from the variable declaration. This is called “target-typednew.” - When to use: When the type is already clear from the context, this reduces redundancy and keeps code concise.

3. Implicitly Typed Local Variable (var)

var c = new Car();

- Explanation: The

varkeyword tells the compiler to infer the variable’s type from the right-hand side (new Car()), socis of typeCar. - When to use: When the type is obvious from the right-hand side or when working with anonymous types or generics.

4. With Object Initializer

All the above forms can be combined with object initializers for setting properties at creation:

Car c1 = new Car { Model = "Sedan" };

Car c2 = new() { Model = "SUV" };

var c3 = new Car { Model = "Coupe" };

Best Practice:

Choose the syntax that makes your code most readable and maintainable for your team. Use explicit types when clarity is needed, and leverage type inference or target-typed new for brevity when the type is obvious.

7.2. Constructors Deep Dive

Constructors are special methods responsible for initializing the state of an object. C# offers several types of constructors and initialization patterns, each serving a distinct purpose in ensuring an object is ready for use.

Instance Constructors: Purpose, Overloading, and Initialization Flow

An instance constructor is a method called to create and initialize an instance of a class. Unlike regular methods, it has the same name as the class and no return type (not even void).

- Purpose: To set the initial state of the object’s instance fields. This often involves taking parameters to provide initial values for these fields.

- Overloading: A class can have multiple instance constructors, as long as each has a unique signature (different number or types of parameters). This allows for flexible object creation based on different initialization requirements.

- Default Constructor: If you don’t provide any instance constructors, C# automatically provides a public, parameterless default constructor. This default constructor initializes all instance fields to their default values (e.g.,

0for numeric types,nullfor reference types,defaultfor value types). If you define any instance constructor, the default constructor is suppressed, and you must explicitly define a parameterless constructor if you need one.

Initialization Flow within an Instance Constructor:

When an instance of a class is created, the following steps occur in sequence:

- Field Initializers: Any field initializers (e.g.,

public int Value = 10;) are executed. These run before the constructor body. - Base Constructor Call: If the class inherits from another class (which all classes implicitly do from

object), the base class’s constructor is called. This happens before the derived class’s constructor body executes. If no explicitbase(...)call is made, the parameterless constructor of the base class is implicitly called (either the default constructor or the one you defined). Note that if the base class has no parameterless constructor, you must explicitly call a base constructor with parameters. - Constructor Body: The code within the body of the current constructor is executed.

class Person

{

public string Name { get; }

public int Age { get; }

// Default constructor, leverages the constructor with parameters

public Person() : this("Unknown", 0)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Person: parameterless constructor: Name={Name}, Age={Age}");

}

// Constructor with parameters

public Person(string name, int age)

{

Name = name;

Age = age;

Console.WriteLine($"Person: constructor with Name={Name}, Age={Age}");

}

}

class Employee : Person

{

public string Position { get; }

// Implicitly calls base()

public Employee()

{

Position = "Unknown";

Console.WriteLine($"Employee: parameterless constructor: Position={Position}");

}

// Calls another constructor in this class

public Employee(string position) : this(position, "Unknown", 0)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Employee: constructor with Position={position}");

}

// Calls base(name, age)

public Employee(string position, string name, int age) : base(name, age)

{

Position = position;

Console.WriteLine($"Employee: constructor with Position={position}, Name={name}, Age={age}");

}

}

// Usage:

Console.WriteLine("Creating Employee():");

var e1 = new Employee();

Console.WriteLine("\nCreating Employee(\"Developer\"):");

var e2 = new Employee("Developer");

Console.WriteLine("\nCreating Employee(\"Manager\", \"Alice\", 35):");

var e3 = new Employee("Manager", "Alice", 35);

// Output:

// Creating Employee():

// Person: constructor with Name=Unknown, Age=0

// Person: parameterless constructor: Name=Unknown, Age=0

// Employee: parameterless constructor: Position=Unknown

// Creating Employee("Developer"):

// Person: constructor with Name=Unknown, Age=0

// Employee: constructor with Position=Developer, Name=Unknown, Age=0

// Employee: constructor with Position=Developer

// Creating Employee("Manager", "Alice", 35):

// Person: constructor with Name=Alice, Age=35

// Employee: constructor with Position=Manager, Name=Alice, Age=35

Object Initializer Notation (new T { ... })

Object initializer notation is a convenient C# syntax that allows you to assign values to public fields or properties of an object after its constructor has been called, all within a single expression. It is purely syntactic sugar; the compiler transforms it into explicit assignments.

public class Product

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public decimal Price { get; set; }

public Product() // Parameterless constructor

{

Console.WriteLine("Product() constructor called.");

}

public Product(int id) // Constructor with ID

{

Id = id;

Console.WriteLine($"Product({id}) constructor called.");

}

}

// Usage:

// Without object initializer

Product p1 = new Product();

p1.Id = 1;

p1.Name = "Laptop";

p1.Price = 1200m;

// With object initializer

Product p2 = new Product // Product() constructor is called first

{

Id = 2,

Name = "Mouse",

Price = 25m

};

// Object initializer with a parameterized constructor

Product p3 = new Product(3) // Product(3) constructor is called first

{

Name = "Keyboard",

Price = 75m

};

How it works (Compiler Transformation):

The compiler transforms p2 = new Product { Id = 2, Name = "Mouse" }; into something conceptually similar to:

Product temp = new Product(); // Calls the constructor

temp.Id = 2; // Then assigns properties/fields

temp.Name = "Mouse";

Product p2 = temp; // Finally assigns the result to the variable

Key Points:

- Execution Order: The constructor is always executed first, followed by the assignments from the object initializer.

- Accessibility: Only public or accessible (e.g.,

internalwithin the same assembly) properties and fields can be set via object initializers. init-only setters andrequiredmembers: Object initializers are particularly useful withinit-only setters (C# 9) to create immutable-like objects where properties can only be set during construction or via an object initializer. They are also crucial for fulfillingrequiredmember (C# 11) initialization guarantees at compile-time. We will revisit these concepts in section 7.4.

Static Constructors: Revisited for Context

While covered in 7.1, it’s worth briefly reiterating static constructors here to clearly contrast them with instance constructors.

- Instance Constructors: Initialize instances of a class. Run every time an object is created. Can be overloaded.

- Static Constructors: Initialize the type itself (its static members). Run at most once. Cannot be overloaded or explicitly called. Their execution timing is guaranteed by the CLR (or optimized by

beforefieldinitif no explicit static constructor).

They both play a role in initialization but operate at different scopes (instance-level vs. type-level).

Primary Constructors (C# 12) for Classes

Introduced in C# 12, Primary Constructors provide a concise way to declare constructor parameters directly in the class (or struct/record) declaration. These parameters are then available throughout the class body, making it ideal for types that primarily initialize their state via constructor arguments.

- Syntax: Parameters are declared directly within the parentheses after the class name.

- Scope and Usage:

- Primary constructor parameters are in scope throughout the entire class body (including field initializers, property accessors, methods, and nested types).

- They are implicitly not fields. If you want to store them as fields, you must explicitly assign them to instance fields or properties.

- They are available to the implicitly generated

ToString(),Equals(),GetHashCode()for records.

- Base Constructor Calls: Primary constructors can directly call a base class constructor using the

base(...)syntax, similar to traditional constructors. - No Other Explicit Constructors: If a class has a primary constructor, every other constructor you define must chain to it.

// Traditional way (for comparison)

public class TraditionalPerson

{

public string Name { get; }

public int Age { get; }

public TraditionalPerson(string name, int age)

{

Name = name;

Age = age;

}

}

// Using Primary Constructor (C# 12)

public class ModernPerson(string name, int age) // Primary Constructor

{

// 'name' and 'age' are available throughout the class body

public string Name { get; } = name; // Assigning to a property

public int Age { get; } = age;

public void Greet()

{

Console.WriteLine($"Hello, my name is {name} and I am {age} years old."); // Directly using parameter

}

// You can still have a parameterless constructor, but it must chain:

public ModernPerson() : this("Default") // Chains to the primary constructor

{

Console.WriteLine("Default ModernPerson created.");

}

public ModernPerson(string name) : this(name, 0) // Overloaded constructor

{

Console.WriteLine($"ModernPerson created with name: {name}");

}

}

// Primary constructor with base call

public class Employee(string name, int age, string employeeId) : ModernPerson(name, age)

{

public string EmployeeId { get; } = employeeId;

public void Work()

{

Console.WriteLine($"{Name} (ID: {EmployeeId}) is working.");

}

}

// Usage and output:

Console.WriteLine("ModernPerson primary constructor example:");

ModernPerson person1 = new ModernPerson("Alice", 30);

person1.Greet();

// Hello, my name is Alice and I am 30 years old.

Console.WriteLine("\nModernPerson() chained parameterless ctor example:");

ModernPerson person2 = new ModernPerson();

// ModernPerson created with name: Default

// Default ModernPerson created.

person2.Greet();

// Hello, my name is Default and I am 0 years old.

Console.WriteLine("\nEmployee example using primary constructor:");

Employee emp1 = new Employee("Bob", 45, "EMP123");

emp1.Greet();

// Hello, my name is Bob and I am 45 years old.

emp1.Work();

// Bob (ID: EMP123) is working.

Primary constructors reduce boilerplate, especially for data-carrying types like records, and improve readability by consolidating parameter declarations with the class definition.

While they are a powerful feature, they are not a replacement for traditional constructors in all scenarios. They shine in cases where the class primarily exists to hold data and where constructor parameters can be directly mapped to properties or fields. However, for more complex initialization logic or when multiple constructors with different signatures are needed, traditional constructors may still be preferable.

Derived Class Constructor Resolution

When a derived class instance is created, a crucial part of the initialization flow (as briefly mentioned in instance constructors) is the calling of a base class constructor. This process ensures that the base portion of the object is correctly initialized before the derived portion.

- Constructor Chaining: Every instance constructor in a derived class must implicitly or explicitly call a constructor in its direct base class. This creates a “chain” of constructor calls, starting from the most derived class and proceeding up the inheritance hierarchy to the

objectclass. - Implicit Base Constructor Call: If you do not explicitly call a base constructor using

base(...), the compiler implicitly adds a call to the parameterless constructor of the base class.- Requirement: This means the base class must have an accessible parameterless constructor. If it doesn’t, you’ll get a compile-time error.

- Explicit Base Constructor Call: You can explicitly choose which base constructor to call using the

basekeyword followed by parentheses containing the arguments for the base constructor. This allows you to pass specific values from the derived constructor’s parameters (or other expressions) to the base class’s initialization logic. - Chaining to Other Constructors: You can also chain to other constructors in the same class using

this(...), note that this eventually leads to a base constructor call as well.

Execution Order of the Constructor Chain:

The most important rule to remember is that the base class’s constructor always executes fully before the derived class’s constructor body begins execution.

Consider the hierarchy Animal -> Dog:

public class Animal

{

public string Species { get; set; }

public Animal(string species)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Animal({species}) constructor called.");

Species = species;

}

public Animal() : this("Unknown") // Chains to the parameterized constructor

{

Console.WriteLine("Animal() default constructor called.");

}

}

public class Dog : Animal

{

public string Breed { get; set; }

// Derived constructor implicitly calls base()'s parameterless constructor

public Dog()

{

Console.WriteLine("Dog() constructor called.");

Breed = "Mixed";

}

// Derived constructor explicitly calls base(string species)

public Dog(string species, string breed) : base(species)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Dog({species}, {breed}) constructor called.");

Breed = breed;

}

// Another derived constructor explicitly calls base()

public Dog(string breed) : base()

{

Console.WriteLine($"Dog({breed}) constructor called.");

Breed = breed;

}

}

Console.WriteLine("--- Creating Dog 1 (implicit base call) ---");

Dog dog1 = new Dog();

// Output:

// Animal(Unknown) constructor called.

// Animal() default constructor called.

// Dog() constructor called.

Console.WriteLine($"Dog 1: {dog1.Species}, {dog1.Breed}\n"); // Unknown, Mixed

Console.WriteLine("--- Creating Dog 2 (explicit base call with species) ---");

Dog dog2 = new Dog("Canine", "Golden Retriever");

// Output:

// Animal(Canine) constructor called.

// Dog(Canine, Golden Retriever) constructor called.

Console.WriteLine($"Dog 2: {dog2.Species}, {dog2.Breed}\n"); // Canine, Golden Retriever

Console.WriteLine("--- Creating Dog 3 (explicit base call to default) ---");

Dog dog3 = new Dog("Poodle");

// Output:

// Animal(Unknown) constructor called.

// Animal() default constructor called.

// Dog(Poodle) constructor called.

Console.WriteLine($"Dog 3: {dog3.Species}, {dog3.Breed}\n"); // Unknown, Poodle

This meticulous constructor chaining ensures that the “base part” of a derived object is always fully initialized and consistent before the derived class adds its own specific state. This is fundamental to maintaining the integrity of the object’s inheritance hierarchy.

7.3. The this Keyword: Instance Reference and Context

The this keyword in C# is a special read-only reference that points to the current instance of the class or struct in which it is used. It is available only within instance members (instance constructors, methods, properties, indexers, and event accessors). Static members, belonging to the type itself rather than an instance, cannot use this.

Referring to the Current Instance’s Members

The most common use of this is to explicitly refer to a member of the current object. While often optional (the compiler usually infers this), it becomes necessary for disambiguation.

public class Calculator

{

private int _result; // Backing field

public int Result // Property

{

get { return _result; }

set { _result = value; }

}

public void Add(int value)

{

// Disambiguation: 'value' is a parameter, 'this._result' refers to the instance field

this._result += value;

// Or: this.Result += value; // Accessing via property

}

public void Reset()

{

this.Result = 0; // Explicitly calling the setter of the Result property on this instance

}

}

Using this explicitly for fields/properties, even when not strictly necessary for disambiguation, can sometimes improve code readability by clearly indicating that a member belongs to the instance.

Passing the Current Instance as an Argument

this is also used when you need to pass a reference to the current object as an argument to a method, especially when implementing patterns like Observer or when a method requires a reference to its caller or context.

public class Logger

{

public void LogActivity(object source, string activity)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[{source.GetType().Name}] {activity}");

}

}

public class Worker

{

private Logger _logger = new Logger();

public void PerformTask()

{

// Pass 'this' (the current Worker instance) as the source of the log message

_logger.LogActivity(this, "Performing a complex task.");

}

}

Worker worker = new Worker();

worker.PerformTask();

// Output: [Worker] Performing a complex task.

Other Contextual Uses

-

Constructor Chaining: As mentioned before,

this(...)is used to call another constructor in the same class, allowing for flexible initialization patterns.public class Person { public string Name { get; } public int Age { get; } // Main constructor public Person(string name, int age) { Name = name; Age = age; } // Chained constructor public Person(string name) : this(name, 0) {} } -

Indexers: The

thiskeyword is used in the declaration of indexers to represent the instance on which the indexer operates.public class StringCollection { private string[] data = new string[10]; // Indexer: allows accessing data like an array (e.g., myCollection[0]) public string this[int index] { get { return data[index]; } set { data[index] = value; } } } -

Events: In event handlers,

thiscan be used to refer to the instance that raised the event, allowing subscribers to know the context of the event.public class Button { public event EventHandler Clicked; public void Click() { // Raise the Clicked event, passing 'this' as the sender Clicked?.Invoke(this, EventArgs.Empty); } } -

Extension Methods: When defining extension methods,

thisis used in the method signature to indicate that the method extends the type specified bythis.public static class ListExtensions { // Extension method for List<T> public static void PrintAll<T>(this List<T> list) { foreach (var item in list) { Console.WriteLine(item); } } } List<int> numbers = new List<int> { 1, 2, 3 }; numbers.PrintAll(); // Calls the extension method // syntax sugar for: ListExtensions.PrintAll(numbers);

In essence, the this keyword serves as an unambiguous reference to the current object, enabling clear access to its members, facilitating constructor chaining, and providing a means to pass the object itself as a parameter. It solidifies the object-oriented paradigm by always pointing back to the specific instance in focus.

7.4. Core Class Members: Properties, Indexers, and Events

Classes define their behavior and expose their data through members. While fields directly store data, C# provides richer abstractions like properties, indexers, and events, which are ultimately translated by the compiler into methods, offering more control and flexibility.

Properties: Compiler Transformation, init-only Setters, required Members, and field Keyword

Properties are member that provide a flexible mechanism to read, write, or compute the value of a private field. They are often referred to as “smart fields” because they encapsulate the underlying data access with methods, allowing for validation, logging, or other logic.

Compiler Transformation (get_, set_ methods):

At the IL (Intermediate Language) level, a property is not a field. It’s a pair of methods: a get_ method for reading the value and a set_ method for writing the value.

public class User

{

private string _userName; // Backing field

public string UserName // Property

{

get { return _userName; } // get_UserName() method

set { _userName = value; } // set_UserName(string value) method

}

}

When you write user.UserName = "Alice";, the compiler emits a call to user.set_UserName("Alice");. When you write string name = user.UserName;, it emits a call to user.get_UserName();.

Auto-Implemented Properties: For simple properties where no extra logic is needed in the getter or setter, C# provides auto-implemented properties. The compiler automatically creates a private, anonymous backing field.

public string Email { get; set; } // Compiler generates a private backing field for Email

Expression-bodied Properties (=> Notation):

C# allows properties to be implemented using the concise expression-bodied member syntax, introduced in C# 6. This uses the => (lambda arrow) notation to define a property whose getter simply returns the result of a single expression.

public class Circle

{

public double Radius { get; set; }

public double Area => Math.PI * Radius * Radius;

}

// Usage:

var c = new Circle { Radius = 3 };

Console.WriteLine(c.Area); // Output: 28.2743338823081

This is functionally equivalent to:

public double Area

{

get { return Math.PI * Radius * Radius; }

}

Key Points:

- Expression-bodied properties are read-only (getter-only).

- They do not have an automatically generated backing field; they compute the value dynamically each time accessed.

- They are ideal for computed properties that return a value based on other fields or properties.

init-only setters (C# 9):

Introduced in C# 9, init-only setters allow a property to be set only during object construction (either via a constructor or an object initializer) and then become immutable. This is incredibly useful for creating objects that are “immutable after creation.”

public class ImmutablePoint

{

public int X { get; init; } // Can only be set in constructor or object initializer

public int Y { get; init; }

// Constructor can set init-only properties

public ImmutablePoint(int x, int y)

{

X = x;

Y = y;

}

}

// Usage:

ImmutablePoint p1 = new ImmutablePoint(10, 20); // OK

// p1.X = 5; // Compile-time error: Init-only property cannot be assigned outside of initialization.

ImmutablePoint p2 = new ImmutablePoint { X = 30, Y = 40 }; // OK: Object initializer works

// p2.Y = 50; // Compile-time error

required members (C# 11):

C# 11 introduced the required modifier for properties and fields. This modifier indicates that a member must be initialized by all constructors of the containing type, or by an object initializer, at compile time. This provides compile-time guarantees that critical properties are never left uninitialized.

public class Configuration

{

public required string ApiKey { get; set; } // Must be initialized

public required Uri BaseUrl { get; init; } // Must be initialized, and then immutable

public int TimeoutSeconds { get; set; } = 30; // Optional, has default

}

// Usage:

// Configuration config1 = new Configuration(); // Compile-time error: ApiKey and BaseUrl are required

Configuration config2 = new Configuration // OK: All required members initialized

{

ApiKey = "mysecretkey",

BaseUrl = new Uri("[https://api.example.com](https://api.example.com)")

};

// You can also initialize via constructor (if a constructor assigns them)

public class AnotherConfig

{

public required string SettingA { get; set; }

public required int SettingB { get; init; }

public AnotherConfig(string a, int b) // Constructor initializes required members

{

SettingA = a;

SettingB = b;

}

}

// AnotherConfig cfg = new AnotherConfig(); // Error if no parameterless ctor

AnotherConfig cfg2 = new AnotherConfig("ValueA", 123); // OK

// AnotherConfig cfg3 = new AnotherConfig { SettingA = "ValueA" }; // Error: SettingB is required

The field keyword (C# 11+ preview):

In C# 11, the field keyword was introduced to provide a way to directly reference the auto-generated backing field from within property accessors (get/set/init). This simplifies scenarios where you need to perform validation or side-effects without recursively calling the accessor itself. Note that as of C# 13, this feature is still in preview and may change in future releases. If you wish to use it, you need to enable preview features in your project settings.

For more details on the field keyword, see the C# Language Specification.

public class Item

{

private string _name; // Traditional backing field

public string Name // Property using traditional backing field

{

get => _name;

set

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(value))

throw new ArgumentException("Name cannot be empty.");

_name = value;

}

}

// Property using 'field' keyword (C# 11+ preview)

public int Quantity

{

get => field; // Reads directly from the auto-generated backing field

set

{

if (value < 0)

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(nameof(value), "Quantity cannot be negative.");

field = value; // Assigns directly to the auto-generated backing field

}

}

}

Before field, you’d typically need to explicitly declare a private backing field for Quantity if you wanted to add logic to its accessors without recursion. The field keyword simplifies this by giving you a direct reference to the compiler-generated backing field.

Indexers

Indexers are a special kind of property that allows objects to be indexed in the same way as arrays or collections. They provide a more natural syntax for accessing elements contained within an object.

- Syntax: Declared using

this[]followed by parameters, much like a method. - Compiler Transformation: Like properties, indexers are compiled into

get_Itemandset_Itemmethods (e.g.,get_Item(int index),set_Item(int index, string value)).

class StringList

{

private List<string> _strings = new();

public int Count => _strings.Count;

public void Add(string s) => _strings.Add(s);

// Single-parameter indexer: get string

public string this[int index] {

get => _strings[index];

set => _strings[index] = value;

}

// Two-parameter indexer: get char at (stringIndex, charIndex)

public char this[int stringIndex, int charIndex] {

get => _strings[stringIndex][charIndex];

}

}

// Usage:

var list = new StringList();

list.Add("Hello");

list.Add("World");

list.Add("CSharp");

// Print strings

for (int i = 0; i < list.Count; i++)

Console.WriteLine($"{i}: {list[i]}");

// Access individual characters

Console.WriteLine($"\nCharacter at (0,1): {list[0, 1]}"); // e

Console.WriteLine($"Character at (1,2): {list[1, 2]}"); // r

// Try to Modify a character

// list[2, 0] = 'c'; // error: read-only indexer

// Output:

// 0: Hello

// 1: World

// 2: CSharp

//

// Character at (0,1): e

// Character at (1,2): r

Events

Events in C# provide a mechanism for a class or object to notify other classes or objects when something interesting happens. They are a core component of the Observer (or Publish-Subscribe) design pattern. At their core, events are built upon delegates (which we will cover in depth in Chapter 11).

- Mechanism: An event acts as a list of delegate instances (event handlers) that are invoked when the event is “raised” or “fired.”

- Compiler Transformation (

add_,remove_methods): Similar to properties, events are not directly fields. The compiler transforms an event declaration into two methods: anadd_method (to subscribe an event handler) and aremove_method (to unsubscribe an event handler). These methods typically add or remove delegates from an underlying delegate field.

// Define a simple delegate for demonstration

public delegate void ValueChangedHandler(string newValue);

// Using Action<T> or Func<T> is often preferred in modern C#

// public event Action<string> ValueChanged;

public class DataStore

{

private string _data;

// Declare an event using the custom delegate

public event ValueChangedHandler DataChanged;

public string Data

{

get { return _data; }

set

{

if (_data != value)

{

_data = value;

// Raise the event

OnDataChanged(value);

}

}

}

// A protected virtual method to raise the event

// This allows derived classes to override the event raising logic

protected virtual void OnDataChanged(string newValue)

{

// Null-conditional operator (?.) is used for thread-safe event invocation

// It checks if DataChanged is not null before invoking

DataChanged?.Invoke(newValue);

}

}

public class DataDisplay

{

public void OnDataStoreDataChanged(string newData)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Display: Data changed to '{newData}'");

}

}

DataStore store = new DataStore();

DataDisplay display = new DataDisplay();

// Subscribe to the event: Compiler calls store.add_DataChanged(display.OnDataStoreDataChanged)

store.DataChanged += display.OnDataStoreDataChanged;

store.Data = "Initial data"; // Output: Display: Data changed to 'Initial data'

store.Data = "Updated data"; // Output: Display: Data changed to 'Updated data'

// Unsubscribe from the event: Compiler calls store.remove_DataChanged(display.OnDataStoreDataChanged)

store.DataChanged -= display.OnDataStoreDataChanged;

store.Data = "Final data"; // No output, as handler is unsubscribed

Custom Event Accessors:

Just as properties can have custom get/set logic, events can have custom add/remove accessors. This is used for advanced scenarios, such as when you want to store event handlers in a custom data structure (e.g., to conserve memory for many events) rather than the compiler-generated delegate field.

using System.ComponentModel; // Using EventHandlerList for custom event storage

public class CustomEventSource

{

// Custom storage for event handlers

private EventHandlerList _eventHandlers = new EventHandlerList();

private static readonly object DataChangedEventKey = new object();

public event EventHandler DataChanged

{

add { _eventHandlers.AddHandler(DataChangedEventKey, value); }

remove { _eventHandlers.RemoveHandler(DataChangedEventKey, value); }

}

protected virtual void OnDataChanged(EventArgs e)

{

EventHandler handler = (EventHandler)_eventHandlers[DataChangedEventKey];

handler?.Invoke(this, e);

}

public void SimulateDataUpdate()

{

Console.WriteLine("Simulating data update.");

OnDataChanged(EventArgs.Empty);

}

}

// EventHandlerList is a system class often used in WinForms/WPF for events

// For a general application, you might implement a custom list of delegates.

In this section, we focused on the fundamental mechanics of events and their compiler transformations. A deeper dive into delegates, event patterns, and common event arguments (EventArgs) will be covered in Chapter 11.

7.5. Class Inheritance: Foundations and Basic Design

Inheritance is a cornerstone of object-oriented programming, allowing you to define a new class (the derived class or subclass) based on an existing class (the base class or superclass). This establishes an “is-a” relationship (e.g., a Dog is an Animal), promoting code reuse, extensibility, and polymorphism.

How the CLR Implements Inheritance

In C#, a class can inherit from only a single direct base class (single inheritance), although it can implement multiple interfaces (multiple interface inheritance, which is distinct from class inheritance). All classes implicitly or explicitly derive from System.Object.

Memory Layout of Derived Class Instances: When you create an instance of a derived class, its memory footprint on the managed heap includes the fields of all its base classes, in addition to its own declared fields. The base class’s fields are typically laid out first, followed by the derived class’s fields.

Conceptual Diagram of Derived Object in Memory:

[Managed Heap]

+-----------------------------------+

| Object Header |

| (MethodTable Ptr) | ----> [AppDomain's Loader Heap]

+-----------------------------------+ +---------------------------+

| Base Class Field 1 | | MethodTable (Derived) |

| Base Class Field 2 | +---------------------------+

| ... | | Ptr to Base MethodTable |

| Base Class Field N | | Derived Field Info |

+-----------------------------------+ | Ptr to Derived Method 1 |

| Derived Class Field 1 | | Ptr to Derived Method 2 |

| Derived Class Field 2 | | ... |

| ... | | (Ptr to V-Table) |

| Derived Class Field M | +---------------------------+

+-----------------------------------+

The MethodTable of the derived class points to its base class’s MethodTable, forming a chain that the CLR can traverse to find inherited members and resolve method calls.

Method Lookup:

When an instance method is called on an object, the CLR uses the object’s MethodTable pointer to find the method. If the method isn’t found directly in the current type’s MethodTable, the CLR follows the chain up to the base class’s MethodTable, and so on, until the method is found or the object class is reached. This process is fundamental to how inherited methods are invoked and will be elaborated upon in 7.10 (Method Resolution Deep Dive).

Use of the base Keyword

The base keyword serves two primary purposes within a derived class:

- Calling a Base Class Constructor: As discussed in 7.2,

base(...)is used in a derived class’s constructor to explicitly invoke a specific constructor of its direct base class. This ensures the base portion of the object is correctly initialized before the derived part. -

Accessing Shadowed Base Class Members: If a derived class declares a member (field, property, or method) with the same name as an inherited member from its base class, the derived member shadows (or hides) the base member. The

basekeyword allows you to explicitly access the hidden base member.public class Vehicle { public string Model { get; set; } = "Generic Vehicle"; public void StartEngine() { Console.WriteLine("Vehicle engine started."); } } public class Car : Vehicle { // Shadows Vehicle.Model (implicit hiding) public string Model { get; set; } = "Sports Car"; // Compiler Warning: implicitly hides inherited member public void Accelerate() { Console.WriteLine("Car accelerating."); } public new void StartEngine() // Hides Vehicle.StartEngine explicitly { Console.WriteLine("Car engine started with a roar!"); base.StartEngine(); // Calls the base class's StartEngine method } public void DisplayModels() { Console.WriteLine($"Car's Model: {this.Model}"); // Refers to Car.Model Console.WriteLine($"Vehicle's Model (via base): {base.Model}"); // Refers to Vehicle.Model } } Car myCar = new Car(); myCar.DisplayModels(); // Output: // Car's Model: Sports Car // Vehicle's Model (via base): Generic Vehicle myCar.StartEngine(); // Output: // Car engine started with a roar! // Vehicle engine started.While

newexplicit hiding is allowed, it’s generally discouraged in favor ofoverridefor polymorphism (discussed in 7.6), as hiding can lead to unexpected behavior depending on the declared type of the reference. Implicit hiding (withoutnew) generates a compiler warning.

Object Slicing Considerations

Object slicing is a concept found in languages like C++ where a derived class object, when assigned to a base class value (not a reference/pointer), can lose its derived-specific data, effectively being “sliced” down to just the base class portion.

In C#, object slicing DOES NOT occur. This is a crucial distinction due to C#’s type system and how reference types are handled. When you assign an instance of a derived class to a base class variable, you are not copying the object’s value or creating a new object. Instead, you are simply assigning the reference to the existing derived class object to a variable of the base class type. The object on the heap remains a full derived class instance.

Key Takeaways (Part 1)

- Object Memory: Class instances (

objects) reside on the managed heap, starting with an Object Header containing a MethodTable pointer linking to type metadata. - Member Types: Understand the fundamental difference between instance members (belong to each object, accessed via

this) and static members (belong to the type, shared by all instances). - Static Constructors: Guaranteed to run at most once per AppDomain, strictly before the first instance creation or static member access.

beforefieldinit: A compiler optimization that allows static fields (without an explicit static constructor) to be initialized earlier, potentially before their first usage, for performance.- Instance Constructors: Initialize individual object instances; they can be overloaded and implicitly or explicitly call base constructors.

- Object Initializers: A C# syntactic sugar (

new T { ... }) that assigns values to properties/fields after the constructor has executed, offering concise object setup. - Primary Constructors (C# 12): A modern, concise syntax for constructor parameters, making them available throughout the class body and streamlining base constructor calls.

- Constructor Chaining: Every derived class constructor implicitly or explicitly calls a base class constructor, ensuring the base object’s initialization completes before the derived object’s.

- The

thisKeyword: Unambiguously refers to the current instance, used for member access, passing the object, and constructor chaining (this(...)). - Properties: Syntactic sugar for

get_andset_methods, offering controlled data access. Includesinit-only setters (C# 9),requiredmembers (C# 11), and thefieldkeyword (C# 11). - Indexers: Provide array-like access (

this[]) to objects, compiled intoget_Itemandset_Itemmethods. - Events: A notification mechanism built on delegates, compiled into

add_andremove_methods. - Inheritance Foundation: Establishes an “is-a” relationship; derived objects include base class fields in their memory layout.

baseKeyword: Used to call base constructors or access shadowed base members.- No Object Slicing in C#: Due to reference type semantics, assigning a derived object to a base class variable only changes the reference type, not the underlying object’s structure on the heap.

7.6. Polymorphism Deep Dive: virtual, abstract, override, and new

Polymorphism, literally meaning “many forms,” is one of the pillars of object-oriented programming. In C#, it primarily refers to runtime polymorphism (also known as dynamic dispatch), where the specific method implementation that gets executed is determined at runtime, based on the actual type of the object, rather than the compile-time type of the variable. This mechanism allows you to write flexible, extensible code that can operate on a base type while invoking specialized behavior in derived types.

The Concept of Runtime Polymorphism

Imagine a drawing application where you have various shapes: circles, squares, triangles. All are Shapes. If you have a list of Shape objects, you want to be able to call a Draw() method on each one, and have the correct Draw() implementation (e.g., Circle.Draw(), Square.Draw()) be invoked, even though you’re holding them all as Shape references. This is precisely what runtime polymorphism enables.

At its core, polymorphism allows a derived class object to be treated as a base class object, yet retain its specific derived behavior for certain methods.

virtual Methods and the override Keyword: Enabling Dynamic Behavior

The virtual and override keywords are the primary tools for achieving runtime polymorphism in C#.

-

virtualKeyword:- Applied to a method, property, indexer, or event in a base class.

- It signals to the CLR that this member’s implementation might be replaced by a derived class.

- Declaring a member

virtualmeans that when it’s invoked through a base class reference, the CLR must perform a runtime lookup to determine the actual type of the object and execute that type’s specific implementation (if overridden). - C# Language Reference: virtual

-

overrideKeyword:- Applied to a method, property, indexer, or event in a derived class.

- It explicitly indicates that this member provides a new implementation for a

virtual(orabstract) member inherited from a base class. - The

overridemethod must have the exact same signature (name, parameters, return type) and accessibility as the base class’svirtualmember. - C# Language Reference: override

Example: virtual and override in action

public class Animal

{

public virtual void MakeSound() // 'virtual' allows derived classes to change behavior

{

Console.WriteLine("Animal makes a sound.");

}

public void Eat() // Non-virtual method

{

Console.WriteLine("Animal eats food.");

}

}

public class Dog : Animal

{

public override void MakeSound() // 'override' provides Dog's specific behavior

{

Console.WriteLine("Dog barks: Woof! Woof!");

}

public new void Eat() // This is hiding, not overriding. See below.

{

Console.WriteLine("Dog eagerly eats kibble.");

}

}

public class Cat : Animal

{

public override void MakeSound() // Another specific behavior

{

Console.WriteLine("Cat meows: Meow.");

}

}

// Usage:

Animal myAnimal = new Animal();

Dog myDog = new Dog();

Cat myCat = new Cat();

Console.WriteLine("--- Direct Calls ---");

myAnimal.MakeSound(); // Output: Animal makes a sound.

myDog.MakeSound(); // Output: Dog barks: Woof! Woof!

myCat.MakeSound(); // Output: Cat meows: Meow.

myDog.Eat(); // Output: Dog eagerly eats kibble.

Console.WriteLine("\n--- Polymorphic Calls via Base Reference ---");

Animal animalAnimalRef = new Animal();

Animal animalDogRef = new Dog();

Animal animalCatRef = new Cat();

animalAnimalRef.MakeSound(); // Output: Animal makes a sound. (runtime type is Animal)

animalDogRef.MakeSound(); // Output: Dog barks: Woof! Woof! (runtime type is Dog)

animalCatRef.MakeSound(); // Output: Cat meows: Meow. (runtime type is Cat)

animalDogRef.Eat(); // Output: Animal eats food. (runtime type is Dog, but 'Eat' is not virtual, so Base's Eat is called)

Explanation: When animalDogRef.MakeSound() is called, even though animalDogRef is declared as an Animal (compile-time type), the CLR determines that the object it actually points to at runtime is a Dog. Because MakeSound is virtual in Animal and overriden in Dog, the Dog’s MakeSound implementation is invoked. This is dynamic dispatch.

For animalDogRef.Eat(), since Eat is not virtual in Animal, the call is resolved at compile time based on the Animal reference. The Dog’s new Eat() method is entirely ignored in this polymorphic context. This highlights the crucial difference between override and new.

base Keyword in Polymorphism: Accessing Base Class Members

When you override a method, you can still call the base class’s version of that method using the base keyword. This is useful when you want to extend the base behavior rather than completely replace it.

class Logger

{

// Virtual property for a suffix

public virtual string Suffix => "";

// Virtual log method

public virtual void Log(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine($"{message}{Suffix}");

}

}

class PrefixedLogger : Logger

{

private readonly string _prefix;

public PrefixedLogger(string prefix)

{

_prefix = prefix;

}

// overrides Suffix too

public override string Suffix => " [logged]";

// Override Log to add prefix and delegate to base

public override void Log(string message)

{

string prefixedMessage = $"{_prefix}: {message}";

base.Log(prefixedMessage);

}

}

Logger logger = new PrefixedLogger("INFO");

logger.Log("Hello world");

// Output: INFO: Hello world [logged]

abstract Classes and Methods: Enforcing Derived Implementations

The abstract keyword allows you to define members that must be implemented by non-abstract derived classes. It’s used to establish a contract.

-

abstractMember (typically Method/Property):- Declared in an

abstractclass. - Has no implementation (no method body).

- Forces non-abstract derived classes to

overrideit. - C# Language Reference: abstract

- Declared in an

-

abstractClass:- A class declared with the

abstractmodifier. - Cannot be instantiated directly using

new. You can only create instances of its non-abstract derived classes. - Can contain

abstractmembers, but doesn’t have to. Can also contain concrete (non-abstract) members. - Serves as a base class that provides common functionality while leaving specific implementations to its descendants.

- A class declared with the

Example: abstract methods and classes

public abstract class Shape // Abstract class: cannot be instantiated

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public Shape(string name)

{

Name = name;

}

public virtual void DisplayInfo() // Concrete virtual method

{

Console.WriteLine($"This is a {Name} shape.");

}

public abstract double GetArea(); // Abstract method: must be overridden by non-abstract derived classes

}

public class Circle : Shape

{

public double Radius { get; set; }

public Circle(string name, double radius) : base(name)

{

Radius = radius;

}

public override double GetArea() => return Math.PI * Radius * Radius;

public override void DisplayInfo() // Can override virtual methods

{

base.DisplayInfo(); // Call base implementation

Console.WriteLine($" Radius: {Radius}");

Console.WriteLine($" Area: {GetArea():F2}");

}

}

public class Rectangle : Shape

{

public double Width { get; set; }

public double Height { get; set; }

public Rectangle(string name, double width, double height) : base(name)

{

Width = width;

Height = height;

}

public override double GetArea() => return Width * Height;

}

// Shape s = new Shape("Generic"); // Compile-time error: Cannot create an instance of the abstract type or interface 'Shape'

Shape circle = new Circle("My Circle", 5);

Shape rectangle = new Rectangle("My Rectangle", 4, 6);

// Polymorphic calls

Console.WriteLine($"Circle Area: {circle.GetArea():F2}"); // Output: Circle Area: 78.54

Console.WriteLine($"Rectangle Area: {rectangle.GetArea():F2}"); // Output: Rectangle Area: 24.00

circle.DisplayInfo();

// Output:

// This is a My Circle shape.

// Radius: 5

// Area: 78.54

abstract methods enforce a contract: any concrete (non-abstract) derived class must provide an implementation for these methods. This ensures that certain essential behaviors are always present in complete (non-abstract) types within the hierarchy.

Method Hiding (new Keyword) vs. Method Overriding

This is a common point of confusion for developers. While override enables polymorphism, the new keyword explicitly hides an inherited member. They behave very differently regarding runtime dispatch.

newKeyword:- Applied to a member in a derived class that has the same name as an inherited member from a base class (whether the base member is

virtualor not). - It tells the compiler, “I know there’s a member with this name in the base class, but I want to declare a new, independent member with this name in this class.”

- Crucially,

newdoes NOT enable runtime polymorphism. The method that gets called depends on the compile-time type of the variable used to make the call, not the runtime type of the object. - C# Language Reference: new Modifier

- Applied to a member in a derived class that has the same name as an inherited member from a base class (whether the base member is

Recommendation: In most scenarios, override is preferred over new for methods that you intend to be specialized in derived classes. Hiding (new) can lead to confusing and error-prone behavior, as the method invoked depends on how the object is referenced. Use new sparingly, typically only when you must introduce a member with the same name as an inherited one but do not intend for it to participate in polymorphism.

What Can Be Virtual and What Cannot

Understanding what types of members can be declared virtual (and thus abstract or override) is crucial:

-

Can be

virtual(andabstract,override):- Instance Methods: The most common use case.

- Instance Properties:

get,set, andinitaccessors can be virtual. You must override both if both exist, or only the one that exists. - Instance Indexers: Similar to properties, their

get_Itemandset_Itemmethods can be virtual. - Instance Events: Their

add_andremove_accessors can be virtual.

-

Cannot be

virtual(orabstract,override):- Static Members: Static methods, fields, properties, indexers, or events cannot be virtual. They belong to the type, not an instance, so there’s no runtime instance to dispatch on.

- Fields: Fields are storage locations, not behaviors. Polymorphism applies to behavior (methods), not data storage directly.

- Constructors: Constructors are special methods for object instantiation. They are not inherited or polymorphic in the same way regular methods are. Their chaining mechanism handles base class initialization (as discussed in 7.2).

- Destructors (Finalizers): These are also special methods. While the CLR manages their execution hierarchy, they cannot be explicitly declared as

virtualoroverridein C# code. - Non-virtual Private Methods: Private methods are not accessible from derived classes, so they cannot be overridden.

7.7. Virtual Dispatch and V-Tables

To truly grasp how runtime polymorphism works, we must delve into the internal mechanics that the .NET CLR employs: Virtual Method Tables (V-Tables). This mechanism is responsible for determining which specific method implementation to call when a virtual method is invoked on a reference to a base type.

Recap: MethodTable (from 7.1)

As established in Section 7.1, every object on the managed heap has an Object Header which contains a pointer to its type’s MethodTable. The MethodTable is the CLR’s internal representation of a type, holding essential metadata and pointers to the type’s methods. For types that use polymorphism, the MethodTable plays a central role in dynamic dispatch.

Virtual Method Tables (V-Tables)

When a class declares virtual methods or overrides virtual (or abstract) methods from its base class, its MethodTable contains, or points to, a Virtual Method Table (V-Table). A V-Table is essentially an array of method pointers. Each entry in this array corresponds to a virtual method that the class implements or inherits.

- Base Class V-Table: The base class defines the initial structure of the V-Table. Each

virtualmethod declared in the base class gets an entry in this table. This entry points to the base class’s implementation of that method. - Derived Class V-Table: When a derived class inherits from a base class:

- It typically gets its own V-Table.

- For any

virtualmethod that the derived classoverrides, the corresponding entry in the derived class’s V-Table will point to the derived class’s implementation. - For

virtualmethods that the derived class does not override, the entry in the derived class’s V-Table will point to the base class’s implementation (or the implementation further up the chain). - This ensures that the V-Table always points to the most-derived implementation for each virtual slot.

Conceptual Diagram of V-Tables and Dispatch:

Let’s consider our Animal and Dog example:

[AppDomain's Loader Heap]

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------+

| Animal MethodTable | | Animal V-Table |

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------+

| ... | ----> | Slot 0: Ptr to Animal.MakeSound() |

| Ptr to Animal V-Table | | ... (other virtual methods) |

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------+

ʌ

|

|

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------------+

| Dog MethodTable | | Dog V-Table |

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------------+

| ... | ----> | Slot 0: Ptr to Dog.MakeSound() |

| Ptr to Dog V-Table | | ... (other virtual methods from Animal) |

+---------------------------+ +-----------------------------------------+

How Dynamic Dispatch Works (The V-Table Lookup Process)

When you call a virtual method (e.g., animalDogRef.MakeSound() where animalDogRef is of type Animal but points to a Dog object), the CLR performs the following steps at runtime:

- Retrieve Object Header: The CLR gets the object reference (e.g.,

animalDogRef) and looks at the object’s header on the heap. - Get MethodTable Pointer: From the object header, it retrieves the pointer to the object’s actual runtime type’s MethodTable (in this case, the

Dog’s MethodTable). - Access V-Table: From the MethodTable, it obtains the pointer to the V-Table of the

Dogtype. - Lookup Method Slot: The CLR knows (from compile-time analysis of the

Animal.MakeSoundmethod) which specific “slot” or index in the V-Table corresponds to theMakeSoundmethod. - Invoke Method: It then retrieves the method pointer from that V-Table slot (which, for

Dog, points toDog.MakeSound()) and invokes that method.

This process ensures that the correct, most-derived implementation of the virtual method is always called, regardless of the compile-time type of the variable holding the object reference. This is the essence of dynamic dispatch.

Performance Implications of Virtual Calls

While powerful, virtual method calls do incur a small performance overhead compared to non-virtual (direct) calls. This overhead comes from:

- Indirection: A virtual call requires an extra layer of indirection (looking up the MethodTable, then the V-Table, then the method pointer) compared to a direct call, where the JIT compiler can simply inline the method call or jump directly to its known address.

- Reduced Inlining Opportunities: Historically, virtual calls were harder for the JIT compiler to inline (i.e., replace the method call with the method’s body directly at the call site), which is a significant optimization.